Tropical Update 11/30/2023 - Lucky Season

Plenty of seasonal reviews are being posted on the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. Although this BMS tropical update will review some of the meteorological highlights of the season, the content will be focused on what the insurance industry needs to know in terms of impacts. Specifically, we will focus on how the 2023 season might have changed our risk perception and, of course, explain some of the luck that has occurred.

In summary, the insurance industry had Mother Nature on its side for 2023 during the Atlantic Hurricane season. The market was on pins and needles at the start of the 2023 season. Insurance and reinsurance rates were coming off significant rate increases as a result of previous severe weather activity and active hurricane landfalls since 2017. Florida seemed to be in turmoil with a flurry of legislative measures to limit losses due to Assignment Of Benefits (AOB). Citizens Property Insurance Corporation had an influx of policies, and it seemed to be just one significant hurricane loss in a populated area away from bankruptcy itself. In fact, many carriers had either closed their doors or decided to limit hurricane risk along multiple coastal states.

The anxiety heading into the season was enhanced as the insurance industry watched a unique combination of two significant climate forcers that could influence the hurricane season in two different ways. In our May BMS Tropical update, we highlighted the wrestling match between a developing strong El Niño and record-breaking sea surface temperature (SST). These warm SSTs can enhance tropical convection. El Niño tends to increase wind shear across the parts of the Atlantic basin, which would limit the ability for tropical convection to form. This unique combination limited the number of historical analogs from which we could gain insight at the start of the season. At this point, it was not obvious if one factor would dominate or if they would essentially balance each other out. We also know that many other climate forcers, like the Saharan air layer, can drive periods of higher or lower-than-normal activity in an overall season.

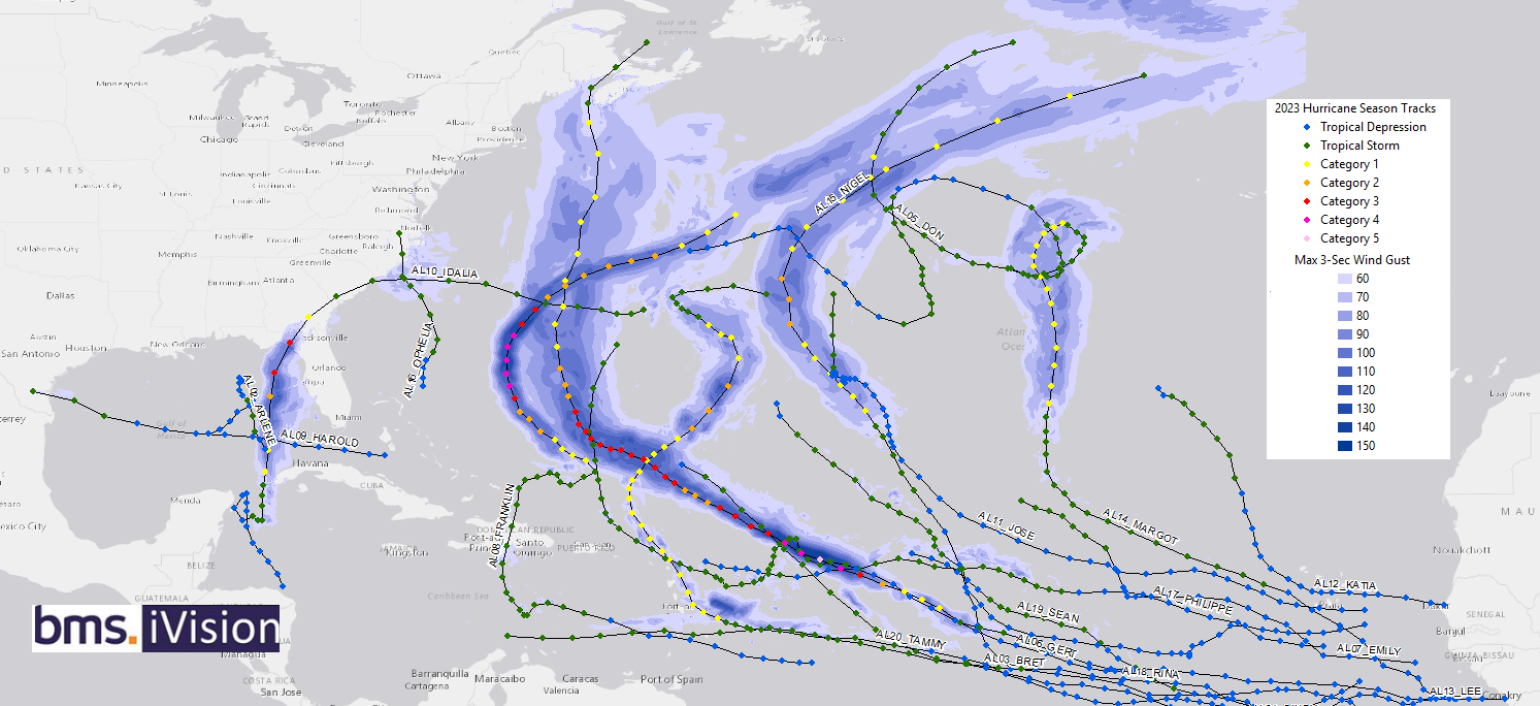

Perhaps the logical place El Niño offered a bit of luck this season stands out in the track map above. As shown, there were no hurricanes in the Caribbean Sea, and with the exception of Idalia for 1.5 days, no hurricanes anywhere west of 72°W. Although sea surface temperatures were near record levels in places like the western Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, El Niño, led to one positive impact too. Specifically, storms were able to turn north well before reaching the U.S. or even the Caribbean, which was good for hurricane landfall, due to the periods of higher wind shear conditions that limited development and a weaker-than-normal Azores High.

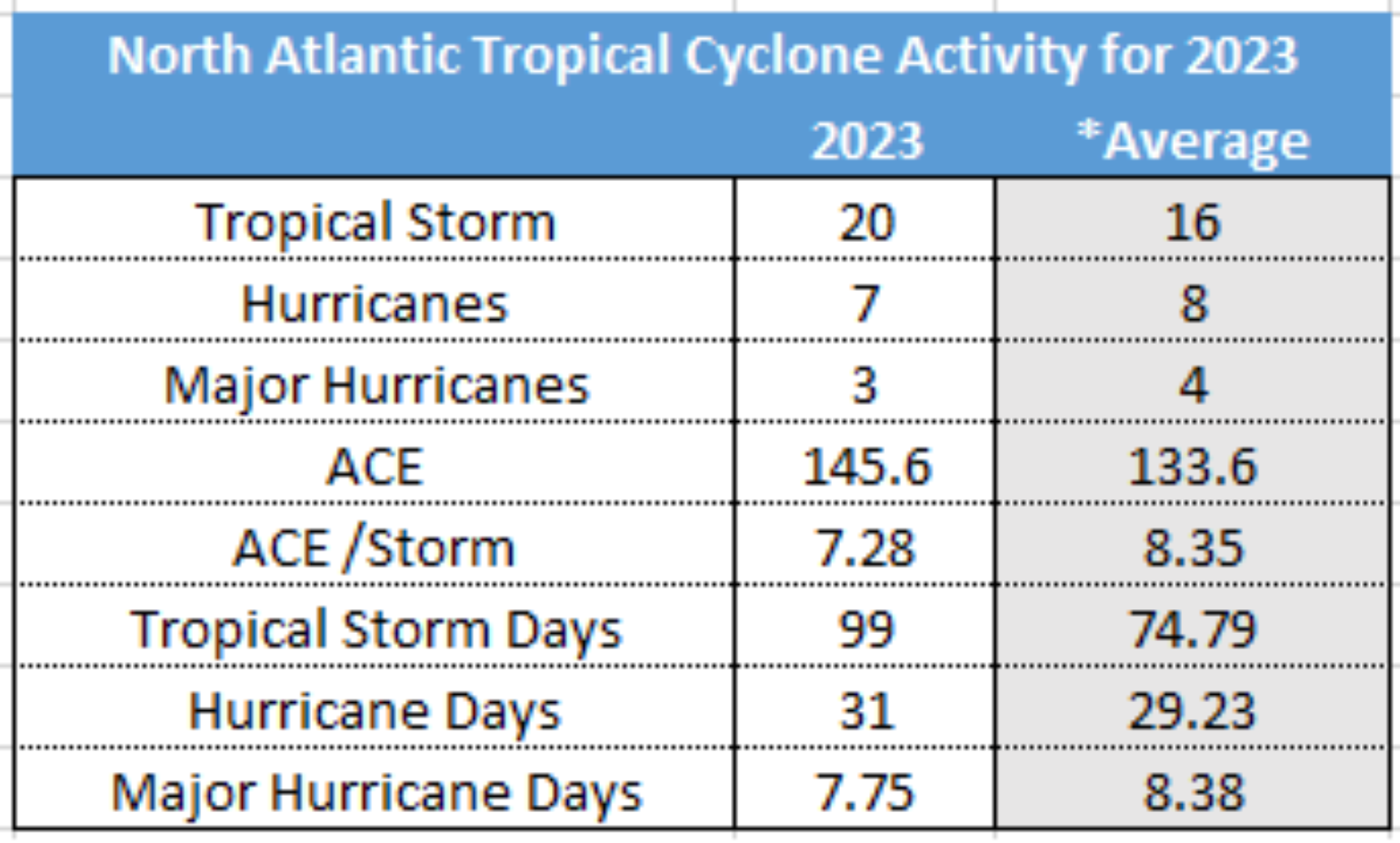

Ultimately, the overall Atlantic Basin is summed up by quantity over quality. Below are the seasonal numbers. The season has produced an above-average number of tropical storms and ACE. With many of the other observations at the 1995-2022 average or just below the average for hurricane and major hurricane development. Moreover, the ACE per individual storm is below the average, as shown in the table below. Blending all these seasonal metrics equates to “a near-normal season.”

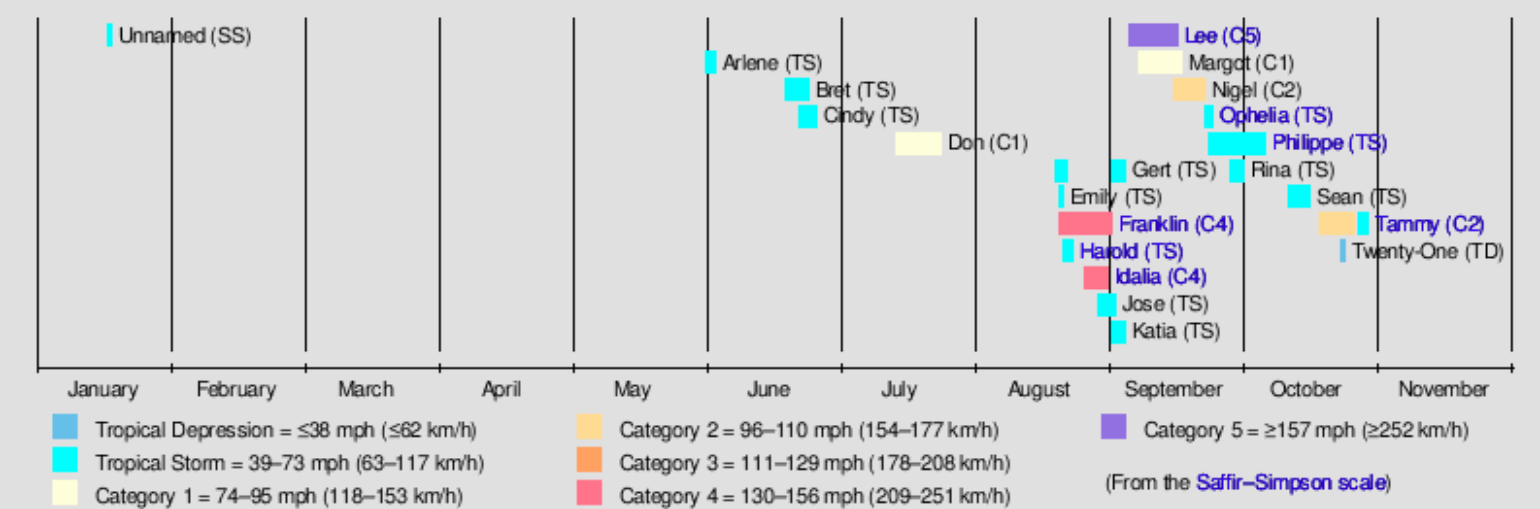

In terms of activity, one aspect of the season that stands out is the overall lucky period that resulted in a relatively long gap in activity heading into the heart of the season from July 26th to August 19th. This was when the basin failed to produce a named storm, yet on the flip side, non-stop named storm activity occurred from August 20th through October 6th, a remarkable 48 days spanning Emily through Philippe.

What Matters Are Landfalls

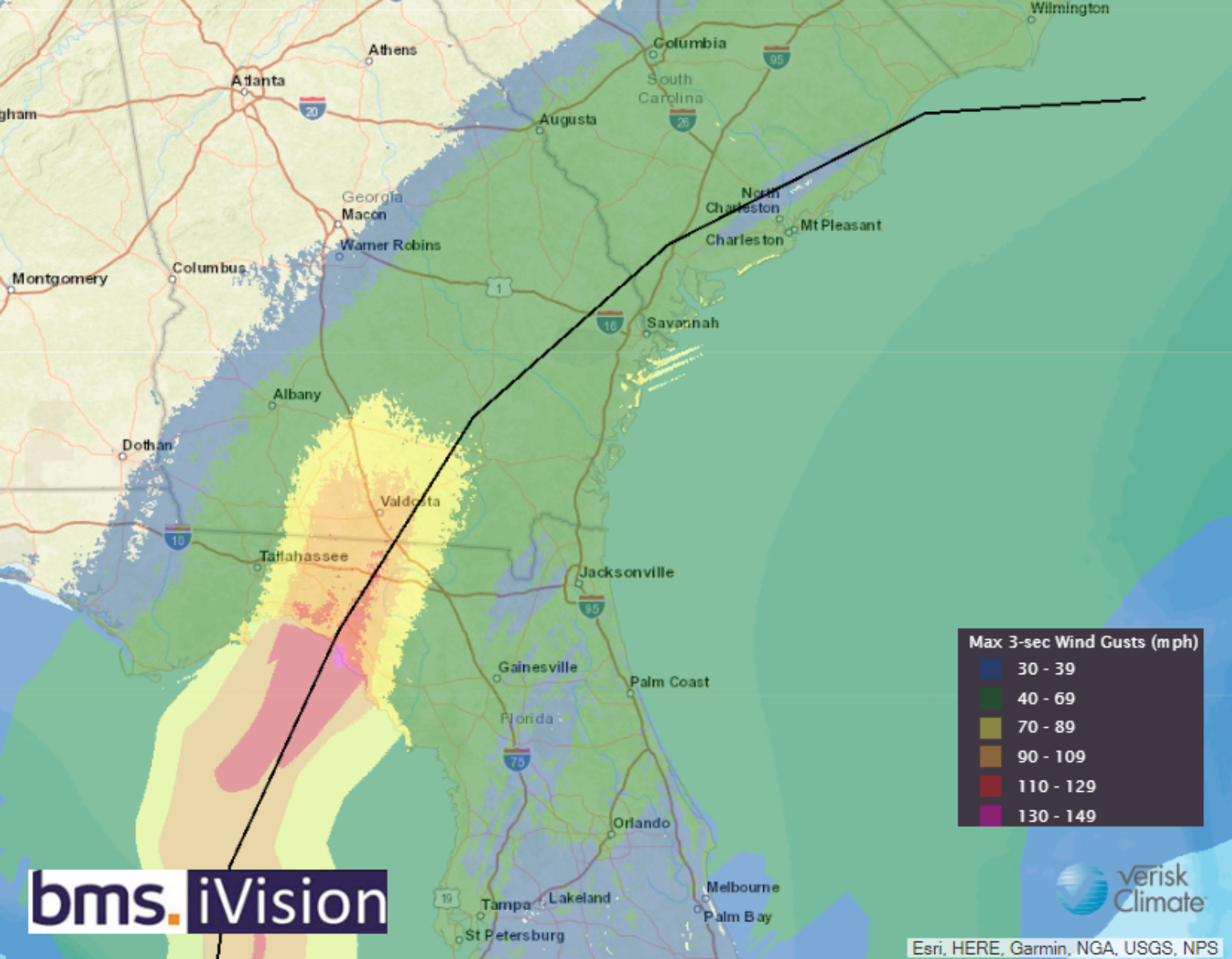

Since 38% of U.S. insurance industry losses over the last 10 years has come from Named Storm or Hurricanes, landfalls are the key to a good or bad season for the insurance industry. This is only second to thunderstorm losses, which account for 44% of the losses. However, not all years will have hurricane losses, and even during an active named storm year like 2023, there can be quite a bit of luck. 2019 is an excellent example of a lucky season. A total of 18 named storms formed that season, with five named storms causing insured losses totaling just over $2B in 2023. One of these storms was Hurricane Dorian, the strongest storm to affect the Bahamas and do a right hook up the east coast of Florida, which clearly would have been a much different story if it were not for some luck that season. If Dorian had hit West Palm Beach and stalled out over Lake Okeechobee, the losses to the insurance industry would have indeed been astronomical. The 2024 season also had a bit of landfall luck for the insurance industry. One of the three major hurricanes this season was Idalia. It formed near the northeastern tip of the Yucatan Peninsula and then rapidly intensified to a Category 4 hurricane as it headed for Florida, then made landfall in the Big Bend region as a Category 3 hurricane just four days after it formed. However, if you remember, some early forecasts showed Idalia having a direct hit on the Tampa Bay / St. Petersburg, which would have topped the $48B loss hurricane Ian had provided the West Coast of Florida during the 2022 season. Unfortunately, the area that ran out of luck was the Big Bend Region of Florida, which had not experienced a major hurricane landfall since 1896. What is maybe even more remarkable for the insurance industry is that Idalia is likely the lowest loss ever to have been experienced by the insurance industry for a hurricane of its magnitude. Using an insurance industry catastrophe model and the historical catalog of events, no events with a 105kt landfall or greater result in a loss of less than $900M. The current loss estimates for Idalia are below $1B, and the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation suggests the loss is closer to $300M. The only closest event in the historical record to Idalia's low loss level at a similar strength would be Bret in 1999, which made landfall in South Texas as a 100kt category 3 hurricane $93M in insurance industry losses. Idalia was 105 kt landfall in Florida.

Remarkably, overall landfall across the Atlantic Basin seemed lucky as well; there were only two hurricane landfalls anywhere in the Atlantic basin all season long: Category 3 Hurricane Idalia in Florida and Category 1 Hurricane Tammy in Barbuda. However, Lee, the season-only Category 5 hurricane, landed in Nova Scotia mid-September. It was technically an extratropical cyclone, but the luck for New England and the long hurricane landfall drought since Hurricane Bob (1991) lives on.

Risk Perception

There continues to be a lot of noise around our overall risk perception regarding hurricanes in a warming world. 2023 likely does not offer up any new insights. We know there is an increase in named storms. It is likely a result of naming more short-lived named storms. The 2023 season had 7 named storms that lasted under 2 days. We know storms seem to be undergoing more frequent periods of rapid intensification. Hurricane Lee, the season-only Category 5 hurricane, intensified very rapidly (85 mph in 24 hours), going from a Category 1 hurricane to a Category 5 hurricane. With that being said, we know we observe storms differently than a decade ago. We likely would not have had constant aircraft data in Lee like we did this year to help aid in this rapid intensification observation. We know our satellite observations are getting more detailed as well.

Maybe the best way to summarize 2023 would be to highlight the recent paper from long-term hurricane MIT researcher Kerry Emanual, who has influenced the insurance industry before and seems to be now taking a different tone from some of his previous research findings in his newest paper, “Limitations of reanalyses for detecting tropical cyclone trends.”

“There is little scientific consensus about trends in global or regional [tropical cyclone] activity, either in the past, as detected in observations or in climate model simulations, or in the future as our climate continues to change.”

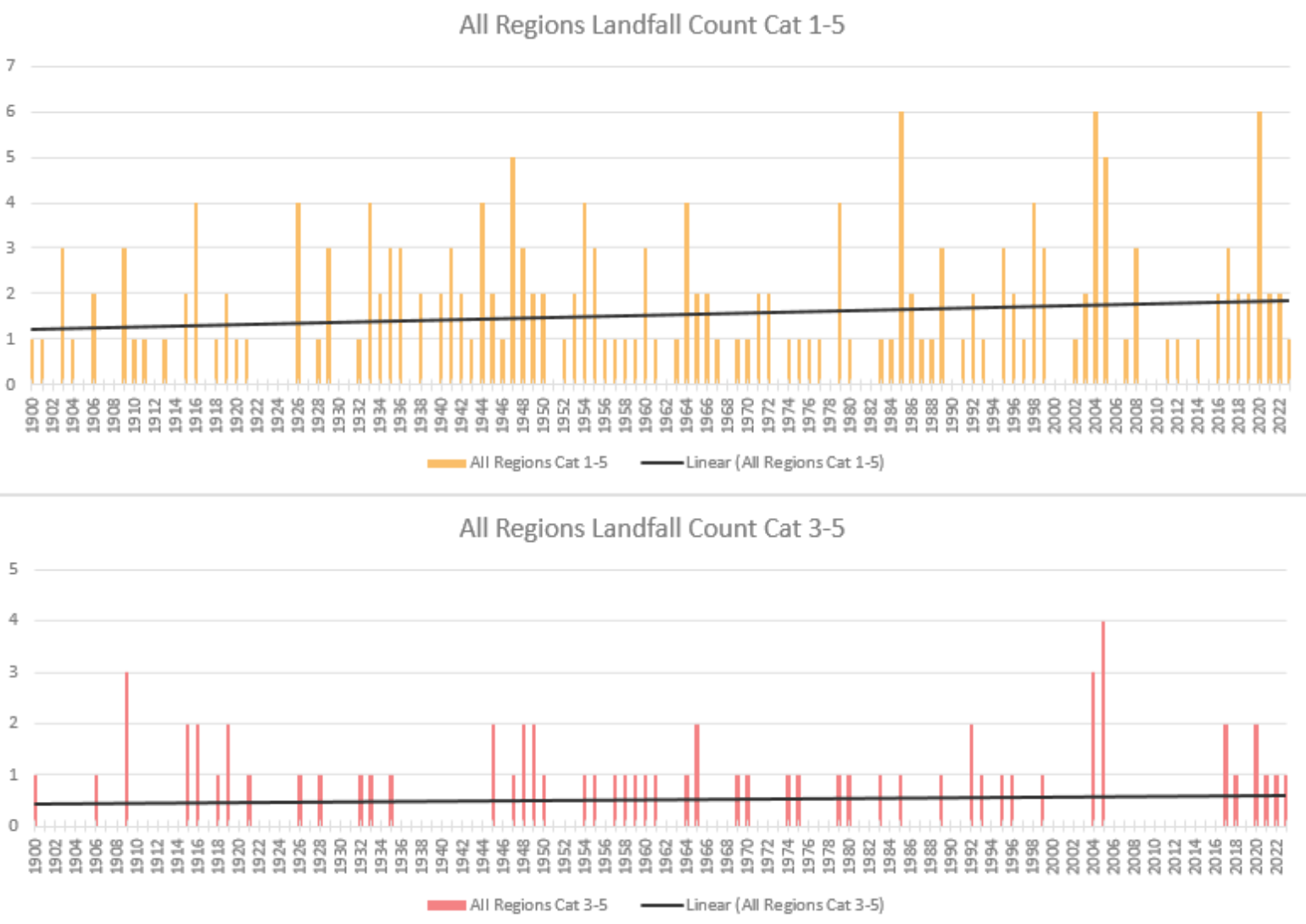

We know the 2023 season will not change the overall trend in landfalls of hurricanes or losses. With an expected landfall rate of 1.6 to 1.8 (depending on the source) hurricanes per year, the 2023 season is nothing unusual. Still, landfall continues to rebound from the historically quiet years between 2006 and 2016.

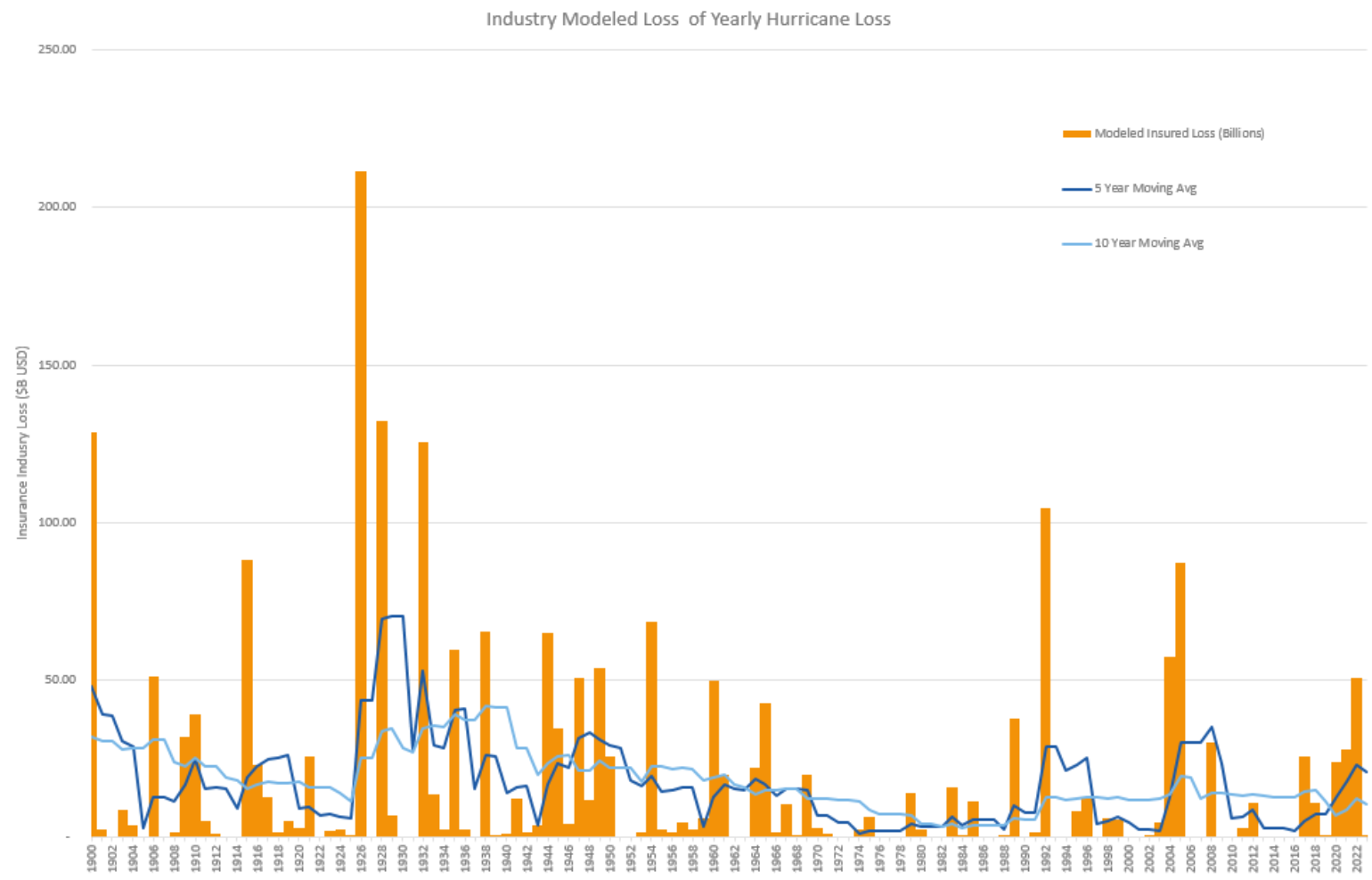

As this post has highlighted, the losses were well below the average industry loss since 2017 of $36B, which shows more considerable yearly losses since 2017. The long-term 10-year moving average loss continues to trend closer to $10B in loss, with the long-term yearly average loss from the model being close to $16B.

Regarding what to expect in 2024, it might be safe to say the insurance industry will be on pins and needles once again. Hopefully, Mother Nature will provide more luck for another season as El Niño relaxes its influences, but sea surface temperatures remain above normal.