Since the last tropical update, overall low activity has warned as expected as general large-scale sinking air and higher wind shear over the Atlantic Basin has taken hold, limiting the development that has occurred over much of the Atlantic Basin. Therefore, within this tropical update, we can take time to reflect on the first anniversary of hurricane Ian. However, we will also take a closer look at what October might have in mind as we close out the last couple weeks of the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season.

Hurricane Ian One Year Later

It is hard to believe that one year ago today, the insurance industry was staring down at the impacts of the largest U.S. hurricane loss in modern history as Hurricane Ian made landfall along the barrier island of Cayo Costa near Punta Gorda, Florida, as a category 4 hurricane. Of course, the landfall area is still healing. For many communities along the Southwest Florida coast, the rebuilding process is a slow and painful reminder of how long it takes to recover from a natural disaster. The good news is that Ian revealed how communities, businesses, and homeowners who might have taken extra steps in building better seem to recover faster. Ian was a great test of building better. It might be the most significant test of how modern building codes will perform, especially since Ian made landfall in the same general area as Hurricane Charley (2004).

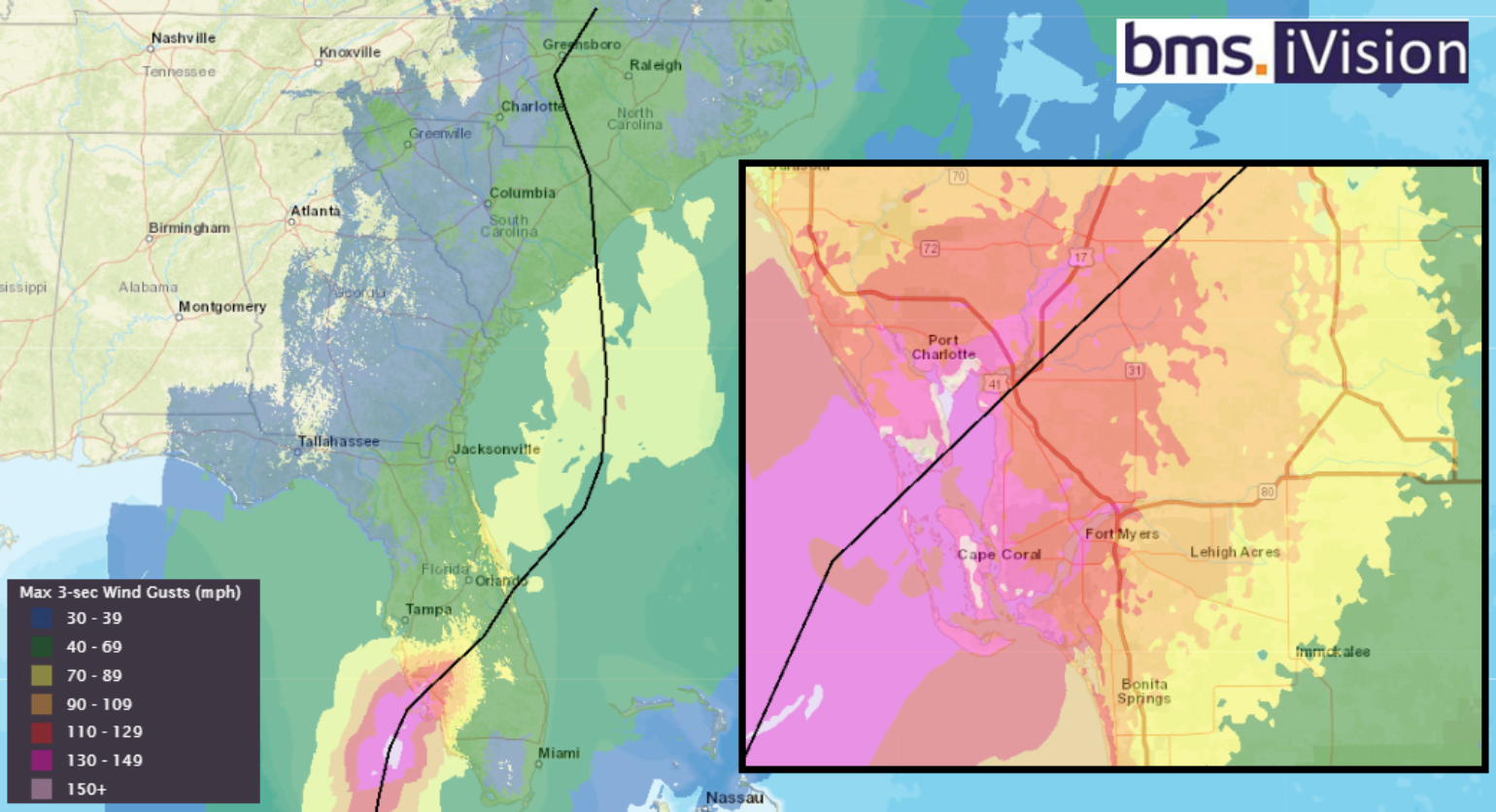

BMS iVision clients can still go back and look at the detailed wind swath of Hurricane Ian in our extensive historical catalog, which suggests areas from Sanibel Island through Port Charlotte and Punta Gorda experienced peak wind gusts between 150-160 mph. These gusts fall just below a design-level wind event per the modern Florida Building Code, which is currently set at a 1 in a 700-year windstorm. Using these past historical events is great for what-if scenarios as carriers shift around their exposure to limit future losses or move into the impacted area to take on additional market share now that many of the structures are being rebuilt to a higher standard.

As with any major hurricane, there will continue to be a post-mortem on the event. Some of these reports can be very valuable to the insurance industry but are often too lengthy to summarise in this short update, so feel free to click the links to read all the details. Still, at a high level, looking at reports from the National Science Foundation’s Structural Extreme Events Reconnaissance (StEER) and the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS), there are already critical takeaways.

As one might expect, these reports detailed that impacts from Hurricane Ian were most severe in the barrier islands from the combination of storm surge and high winds, with many buildings completely washed away. Some buildings were left to deal with significant scour and eroded foundations. Several mobile/manufactured home parks on the barrier islands fared poorly, offering little protection.

Time and time again, critical infrastructure is impacted. In this case, the causeways out to the barrier islands were washed away in multiple locations, prolonging the recovery efforts. Getting infrastructure back online is critical. With no power lines, telephone lines, and damaged roads, the recovery efforts are much slower.

One positive comment from StEER, who travels the world looking at disasters, mentions that relative to other Category 4 storms, the damage was better than what one might expect from other wind storms of this magnitude. In fact, this could be due to a combination of actual wind intensity being less than Category 4 at the surface at landfall and the improvements in building construction that have occurred since Hurricane Charley struck 18 years earlier.

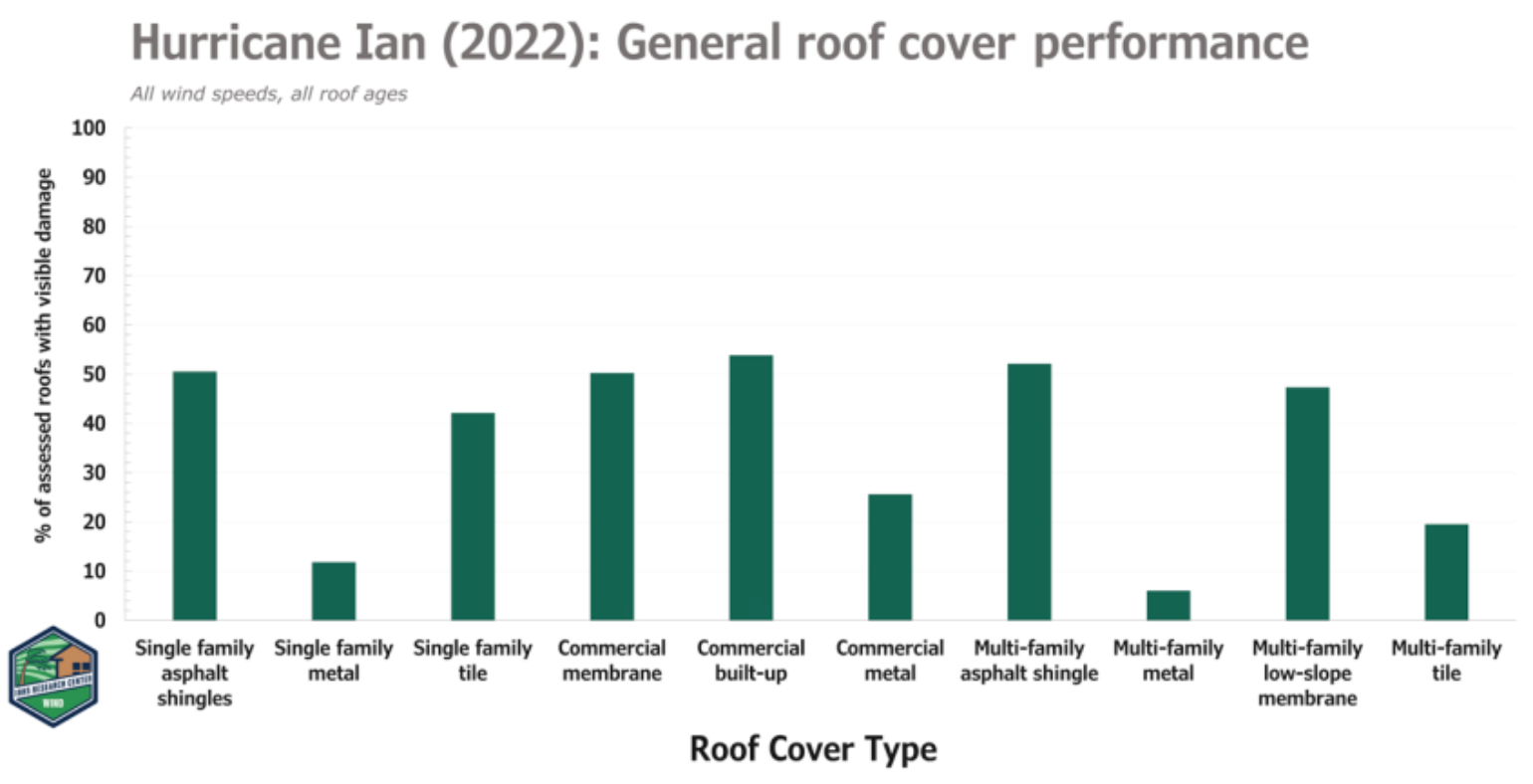

The IBHS has provided some initial insights into roof covering and will create additional reports on other structural damage and performance on the modern Florida Building code. They have looked at 3,646 single-family homes, 327 light commercial buildings, and 133 multifamily structures (e.g., condos, town homes, and duplexes). At a high level, it seems to be similar to some of their findings from the hurricanes of 2020 (Laura and Delta) and how structures performed after Rita (2005).

As expected, asphalt shingles drove the bulk of residential roof cover damage. One out of every two asphalt shingle roofs assessed had detectable damage. Damage rates to asphalt shingle roofs were similar to that observed following Hurricane Charley (2004), illustrating that little progress has been made in improving the wind resistance of asphalt shingles. If an asphalt shingle roof was 10 years or older, the probability of damage in maximum gusts of 110 mph and higher was over 75%.

The IBHS found in their study that steep-slope metal roofs performed very well, with a damage rate near 12%, but also showed that damage to metal roofing often resulted from the failure of another building element, such as a carport or a lanai. This highlights that a building is a system, and the entire system needs to be hardened; otherwise, the system fails.

Where will the losses end up?

$17.3B in losses on 739,771 claims as of late July for the state of Florida Office of Insurance Regulation (FOIR) have been recorded. There needs to be a 179% increase from the FOIR number to reach the level of loss from another industry standard loss estimate for the state of Florida. Though the most official source we might have is from FOIR, which requires companies to submit losses. The FOIR reports 86% of these claims (about 637,000) are closed – 70% with payment and 30% without. The FOIR recently issued an Enhanced Data Call to insurance companies, which was due yesterday (September 27). So, the insurance industry will have even more detailed data to work.

According to Lisa Miller Associate, in the one year between March 2022 and March 2023, Florida courts saw 59,400 cases filed, or 276 cases per 100,000 people. There are still lots of questions about how much of the pending litigation was handled prior to the control insurance litigation passed this past winter. In Citizen policies, just 3% of claims at First Notice of Loss take the form of lawsuits now, down 72% compared to 2022. Assignment of Benefits (AOB) cases have decreased by 33%, but we know there will continue to be loopholes with unknowns abound, and changing laws and building practices often take years, if not decades, to establish. Others across the insurance industry have initially estimated to be between $32B and $63B with damage. There still seems to be a long road to seeing the ultimate loss.

With every catastrophic event, there is a learning opportunity, and there has been no shortage of them since 2017. Still, Ian was unique in that it impacted a very large coastal population that, by definition, was a disaster by design with all the ocean access canals around Cape Coral. This event will likely shaped the insurance industry and communities well away from the epicenter of southwest Florida in the future for future generations.

Tropical Update View into October

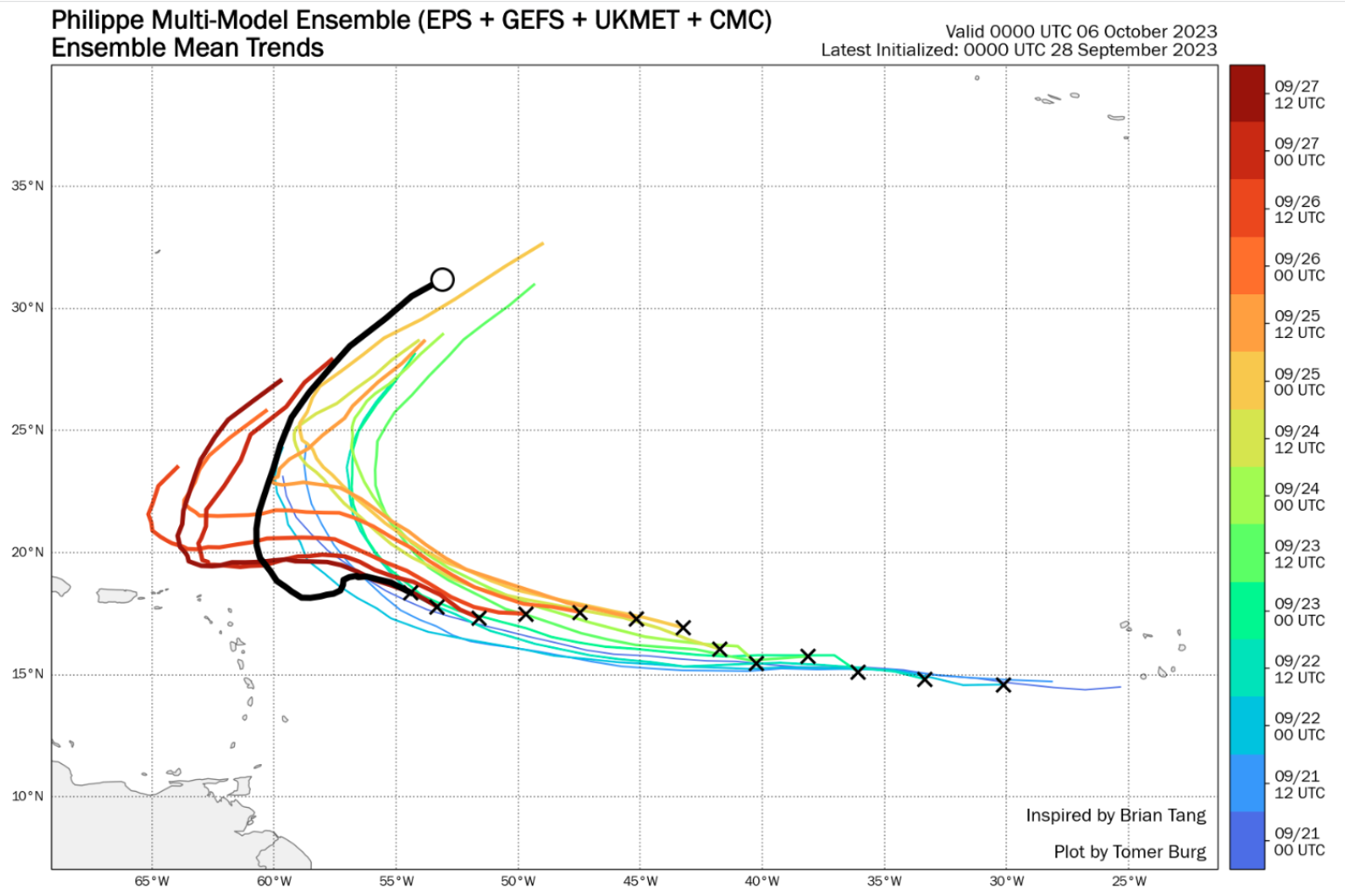

Though no medium-term threats exist to Florida or the continental U.S., the eastern Main Development Region still produces tropical troubles. Suppose you have noticed the National Hurricane Center forecast for tropical Storm Philippe instead of recuring east of Bermuda. The newest forecast takes the system near the Caribbean Islands over the next five days, a large forecast swing, so significant errors can still occur with named storm forecasts.

Even though the sea surface temperatures are ideal for named storm development and helping to some degree with the recent named storm development, you need a combination of ingredients to come together for a robust named storm into a strengthening hurricane. Right now, those ingredients are not present. Due to upper-level subsidence and higher wind shear, Philippe is struggling. To some extent, a well-organized tropical wave halfway between West Africa and the Lesser Antilles labeled Invest 91L is struggling. Invest 91L is forecasted to become named storm Rina by tomorrow. At this time, 91L will probably not threaten any land areas. However, uncertainty remains in how quickly it organizes. Furthermore, potential interactions with Philippe mean it could move towards the northern Lesser Antilles in 5 to 7 days. Regardless, the Caribbean islands should monitor the development of Philippe and Invest 91L over the next week. Though it still appears likely that Philippe will be a rainmaker to the islands and Invest 91L will be drawn north by a west-central Atlantic trough of low pressure and track that system east of Bermuda.

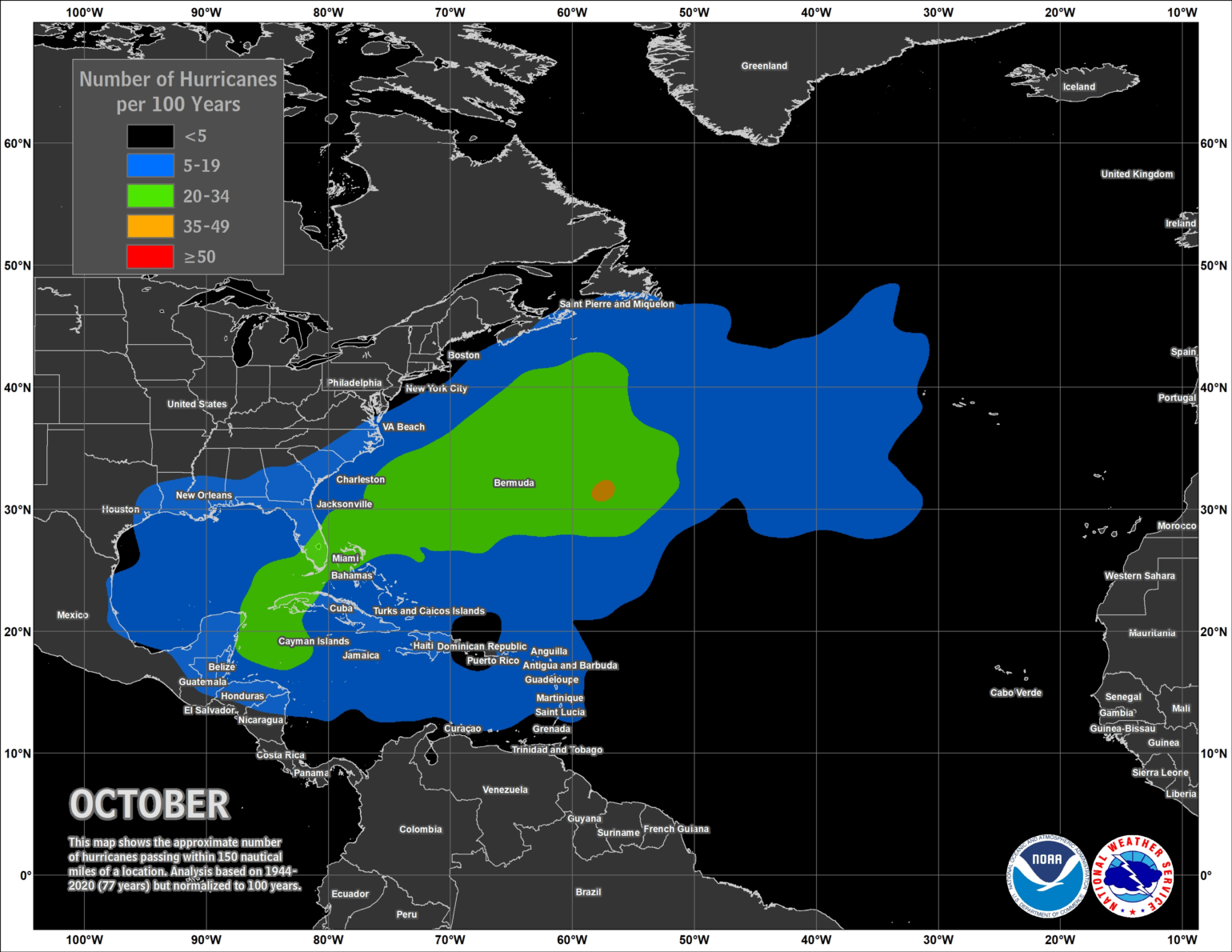

Overall, there is still a significantly elevated risk of activity starting in the second week of October; the upper-level air pattern seems more conducive for named storm activity. In a way, this week's weather pattern could offer hints to what might happen in October. Earlier in the week, the NHC highlighted an area of disturbed weather in the southern Gulf of Mexico. This moisture has been working along an upper-level low, triggering disorganized showers and storms from North Florida to the western Caribbean. Along with climatology, there is always a concern that a tropical disturbance could form in this region towards the end of the season. Given the continued warmth of the SST in this region and the Gulf of Mexico, the areas must be monitored for more development this season. However, the good news is that there is nothing on the radar that would threaten the U.S. Coastline in the next 15 days.