BMS Tropical Update 08/21/2023

What is going on in the tropics? Actually, nothing unusual at all. The late Bill Gray, a world-renowned seasonal hurricane forecaster from Colorado State University, always denoted August 20th as the start of the climatologically most active portion of the Atlantic hurricane season that runs until October 10th. Since 1991, 70% of all major hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin occur after August 20th. In fact, hurricanes account for 62% and 51% of all tropical storms.

What is more alarming to the insurance industry is that over the last ten years, 98% of all insurance losses come after August 20th, totalling $218B in insurance industry loss over 25 hurricanes and tropical storms.

Like clockwork, the Tropical Atlantic and East Pacific have come alive. This BMS Insight will not focus on any one particular storm, but focus on the overall pattern and what the future risk holds as we move towards the peak of the season, which is only 20 days away.

Hillary Impacts

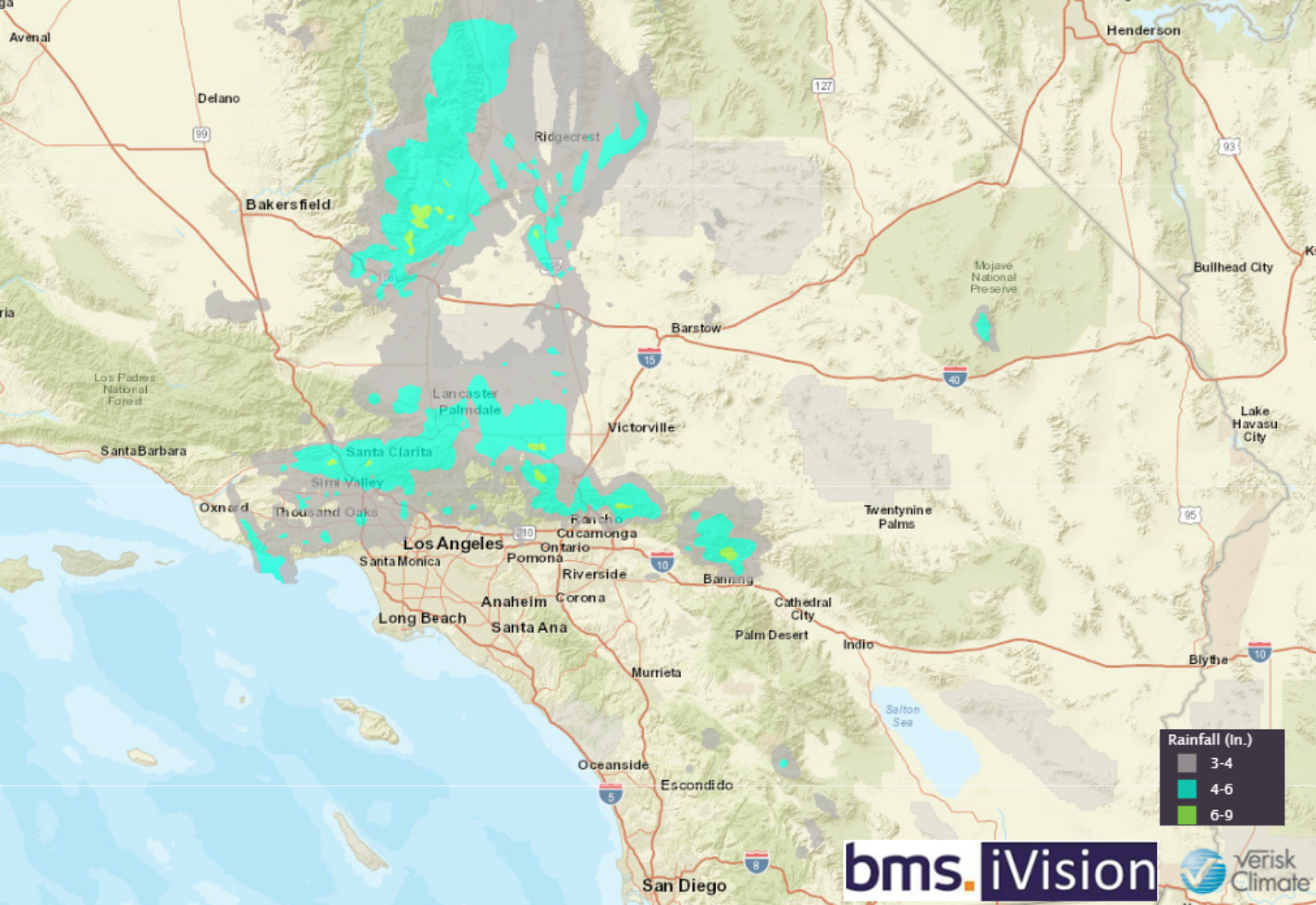

Much of the recent attention has been on Hurricane Hilary in the East Pacific, which made landfall in Baja, California, and tracked into the very populated portion of Southern California. This has produced some historical rainfall over many urban areas with poor drainage. The peril of concern has been flooding. Overall, according to FEMA data, flood insurance take-up rates for much of California, minus a few counties around the Sacramento River basin, have a take-up rate of less than 5%. Many counties have a take-up rate of less than 1%, which includes the desert area and areas like Los Angeles and San Diego counties. In general, this rain is a good thing for future wildfire risk as it comes at the right time since the areas had started to dry out a bit and are headed into the peak wildfire season. One concern is that there could be localized debris flow losses from recent wildfires, but the insurance industry routinely denies coverage to homeowners who suffer damage due to flooding and mudslides caused by wildfires. The insurers typically cite flood, mudslide, and earth movement exclusions. Regardless Hilary will cause wide flooding losses that are likely underinsured, but it should not be a significant insurance loss event as the primary cause of loss would be flooding, and the winds have been manageable by post-tropical storm standards.

Atlantic Storms

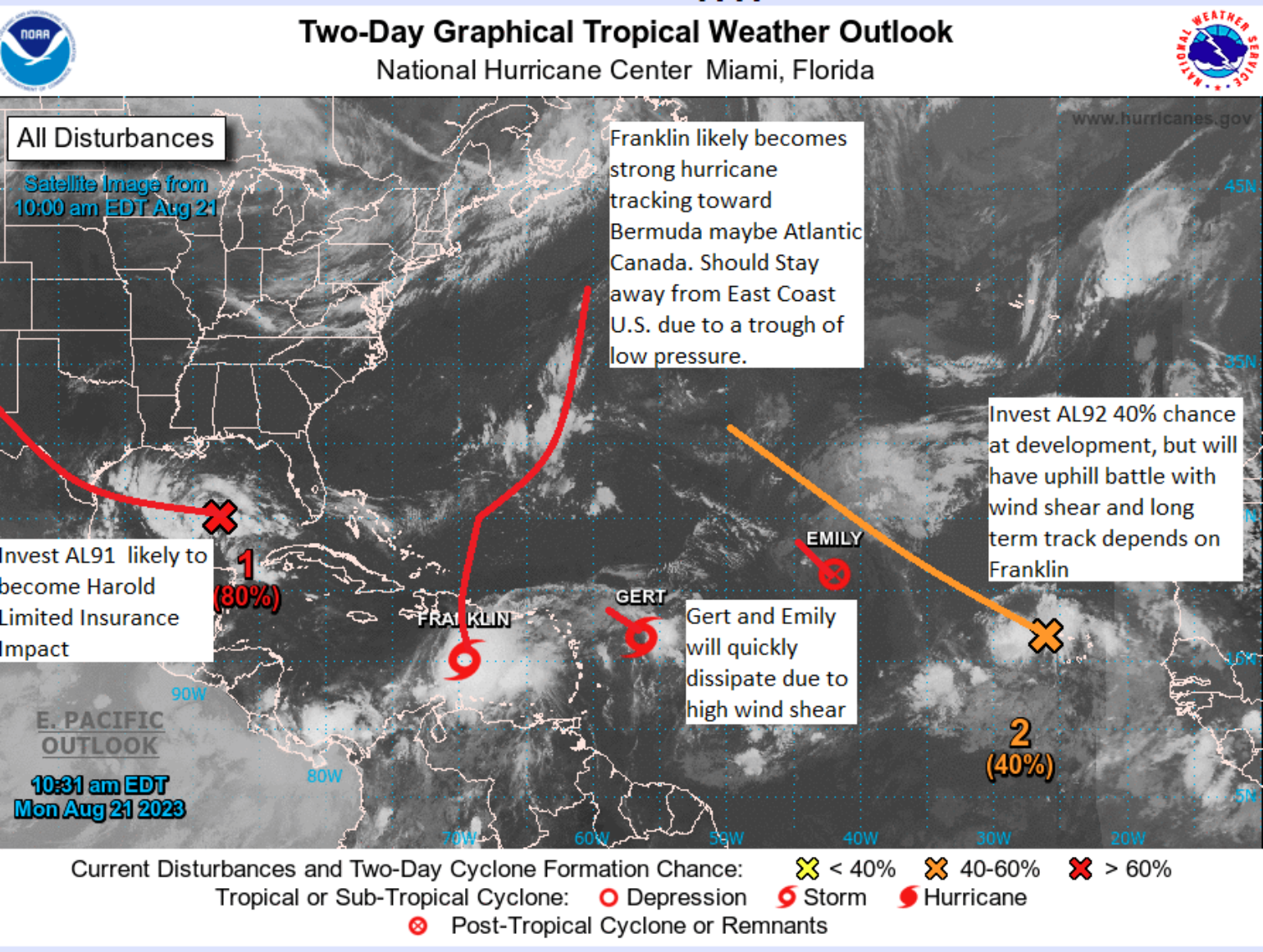

With Hillary gone, the attention will shift to the Atlantic, which has lit up like a Christmas tree if you are paying attention to the National Hurricane Center (NHC) disturbance outlook tracker over the last week. In fact, over a 24-hour period this weekend, the naming became quite prevalent. For only the third time on record (since 1851), three Atlantic tropical cyclones formed over 24 hours (Gert, Emily, Franklin). This has only occurred two other times, on August 22, 1995, and August 15, 1893. Last night with the formation of Tropical Storm Franklin, the 7th named storm of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season to date (subtropical storm formed in Jan), has been named. Since 1960, 7 other years have had 7+ named storms by August 20th: 1995, 2005, 2011, 2012, 2017, 2020, 2021. Some of those years should raise an eyebrow for the insurance industry.

Later today or tomorrow, Harold will form in the Gulf of Mexico, highlighting that the basin is indeed moving towards the season's climatological peak.

Harold and Idalia are new names on this list, replacing Harvey and Irma from six years ago. We cannot forget that the “I” storm is the most retired letter for named storms. Hopefully, this year, Idalia gets assigned to the invest AL92 in the far Eastern tropical Atlantic and lives to see another season six years from now.

The first order of concern should be AL91, now Potential Tropical Cyclone Nine, which is in the Western Gulf of Mexico. The NHC is giving this an 80% probability that it will become Harold. It is a disorganized mass of thunderstorms slowly making its way westward. Model guidance suggests it could acquire a closed surface circulation and become a tropical depression or named storm, but no models develop it into anything troublesome. This will likely be just a rainmaker which is welcome news for the areas currently in drought over parts of Texas. Given the all-time record warm water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, we obviously cannot tune it out completely. Widespread areas of 32-33°C water are unheard of in the Gulf, but it is what we have got right now. This system should reach southern Texas or northern Mexico on Tuesday, and the coastline has a history of quick spin-up storms. Suppose this area of concern does develop into a named storm. In that case, it should be a manageable event for the insurance industry; however, Texas has already seen very high losses from severe weather events this year. Overall, the wind and rainfall should be limited, and these layers will be posted in BMS iVision to help BMS Re client understand these impacts.

The second order of concern is Tropical Storm Franklin, currently south of Hispaniola. There is agreement among the models that Franklin will turn north toward Hispaniola. After exiting the Caribbean on Wednesday, there is a really good chance of intensification as it removes itself from the overall hostile conditions of the Caribbean. Franklin will likely become the basin's second hurricane on its path northward. In fact, this area has higher wind shear due to El Niño and areas of drier and dust air, which have kept the basin relatively quiet until this past weekend.

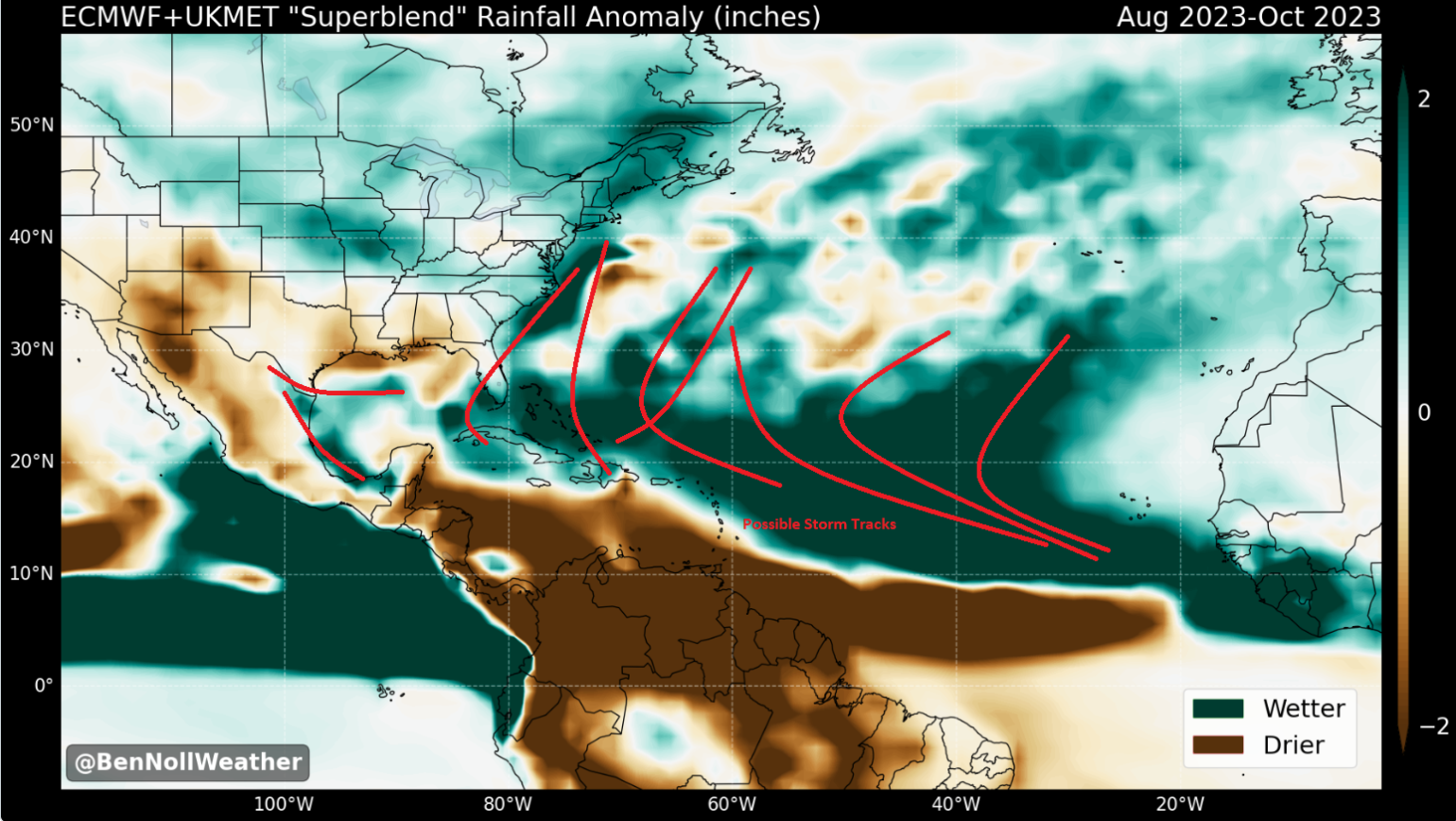

Much attention will be on a very strong ridge of high pressure over the central U.S. this week, bringing record temperatures and almost unbearable heat index readings. This ridge of high pressure will be critical to the future track of Franklin. The longer-range forecast calls for this ridge of high pressure to shift back to the Southwest U.S., allowing a bit of a trough to form along the East Coast, partly due to Hilary's influence on the jet stream. This should protect the East Coast and will be important in keeping the U.S. landfall free during this hyperactive period.

Though, do not forget about the other areas of concern with tropical storms Gert and Emily and invest 92 in the eastern tropical Atlantic. After the next few days, wind shear should increase substantially and be the demise of Gert and Emily, with Emily holding on longer as a tropical depression. Invest 92 will likely follow Emily, but a lot will depend on what happens with Franklin later this week and into this weekend. For that reason, this system needs to be watched as it makes its way into the Atlantic as possibly the “I” storm Idalia.

Approaching Peak Season (Sept 10th)

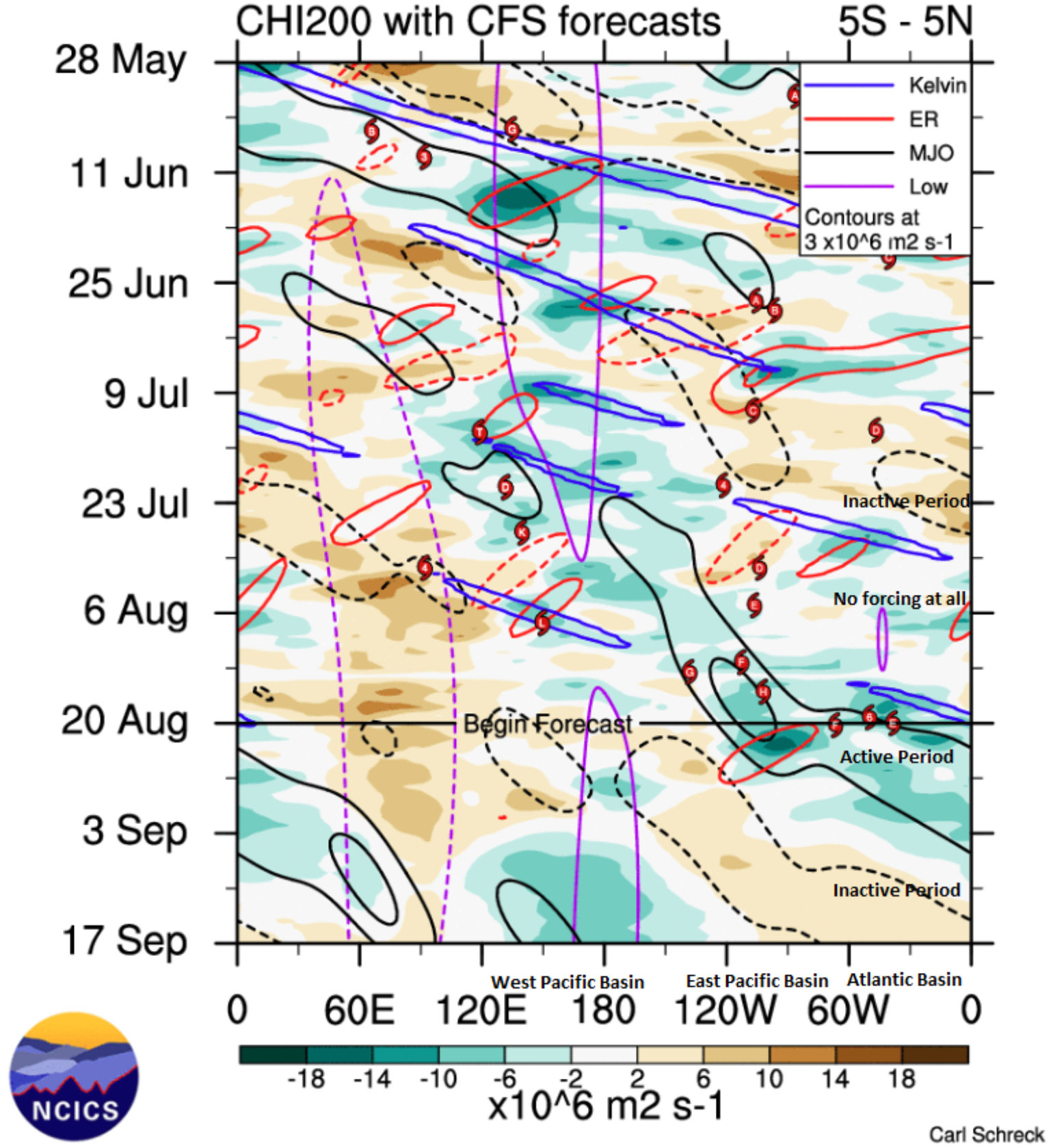

Although we have taken three names off the 2023 list, with Harold likely tonight in the Gulf, the overall basin Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Index is right where it should be climatologically. Gert and Emily will be dissipating, and if Harold develops in the Gulf of Mexico, it likely will not have much time to add to the ACE. Subsequently, if the basin hurricane forecasting community wants to verify an active Atlantic Hurricane season like they are, they better hope Franklin and 92L ad some significant ACE over the next week, as this might be the best chance at activity due to the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO).

The MJO, to simplify its definition, is an eastward-moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds, and pressure originating from the Indian Monsoon that traverses the planet in the tropics and returns to its initial starting point in 30 to 60 days. This is a well-known method of linking intra-seasonal periods of enhanced and suppressed tropical cyclone activity, and like clockwork along with climatology, the basin has come alive.

For the first time this summer, a legitimate MJO wave is moving over the Atlantic basin for the first time. This is the primary cause of the flurry of activity over the deep tropics. This comes at a time when wind shear has been above average over much of the Main Development Region (MDR) being boosted by El Niño, but also plenty of dry air and dust to limit development for most of July and August thus far.

The seasonal forecast is still very bullish on an active season, and most of this is based on warmer sea surface temperatures, but as July and August have shown, it takes more than just warm water to produce a named storm. This MJO may have difficulty keeping the naming activity up while a relatively quick return to robust El Niño-like forcing. Ultimately, this likely translates to about a 2 to 3 week window of above-normal Atlantic TC activity before basin-wide conditions potentially turn less favorable than normal in September.

Where storms might track is of most interest to the insurance industry, we can use the rainfall anomaly to understand better areas that will see more rainfall, which in the months of August through October tend to be named storms. Also here is some other analogs based on Sea Surface temperature (SST) the insurance industry might want to check out.

Overall, at this time, there are no major areas of concern for insurance loss outside of Texas this week. Franklin could impact Atlantic Canada later next week. The peak of the season could be quiet, but October has been an active month for storms forming in the Gulf of Mexico, and the water is very warm in this area, so this is maybe the biggest concern as the season closes.