Calm Before The Storm

Have you heard the saying, “the calm before the storm”? This is very much what that saying means, given that it has been 25 days since Tropical Storm Chirs formed in the Gulf Of Mexico, leading to many questions about what happened to all this forecasted hurricane activity. Of course, Beryl roared to life on June 28th and became the earliest Category 5 hurricane on record. Beryl's long track and intensity rocketed the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Index to record levels. Thankfully for the insurance industry, Beryl did not have more time to intensity before its final landfall on the central Texas coastline, where the average of all U.S. insurance loss estimates is about $2.3B. After Hurricane Beryl finally dissipated on July 10th, the Atlantic basin has been largely void of tropical troubles. Given the forecast model, there will likely be no new tropical development for the month of July. Worldwide, the Northern Hemisphere has only produced eight named storms this year, which is near record low activity in the Northern Hemisphere.

However, this lull in activity is not unusual for the Atlantic basin. We have seen this before and should not forget this happens. The very active season of 2021 had a similar lull between hurricane Elsa, which ended on July 9th, and was later followed by the formation of Tropical Storm Fred on August 11th. In fact, the insurance industry is very familiar with the landfall later in the season with hurricane Ida.

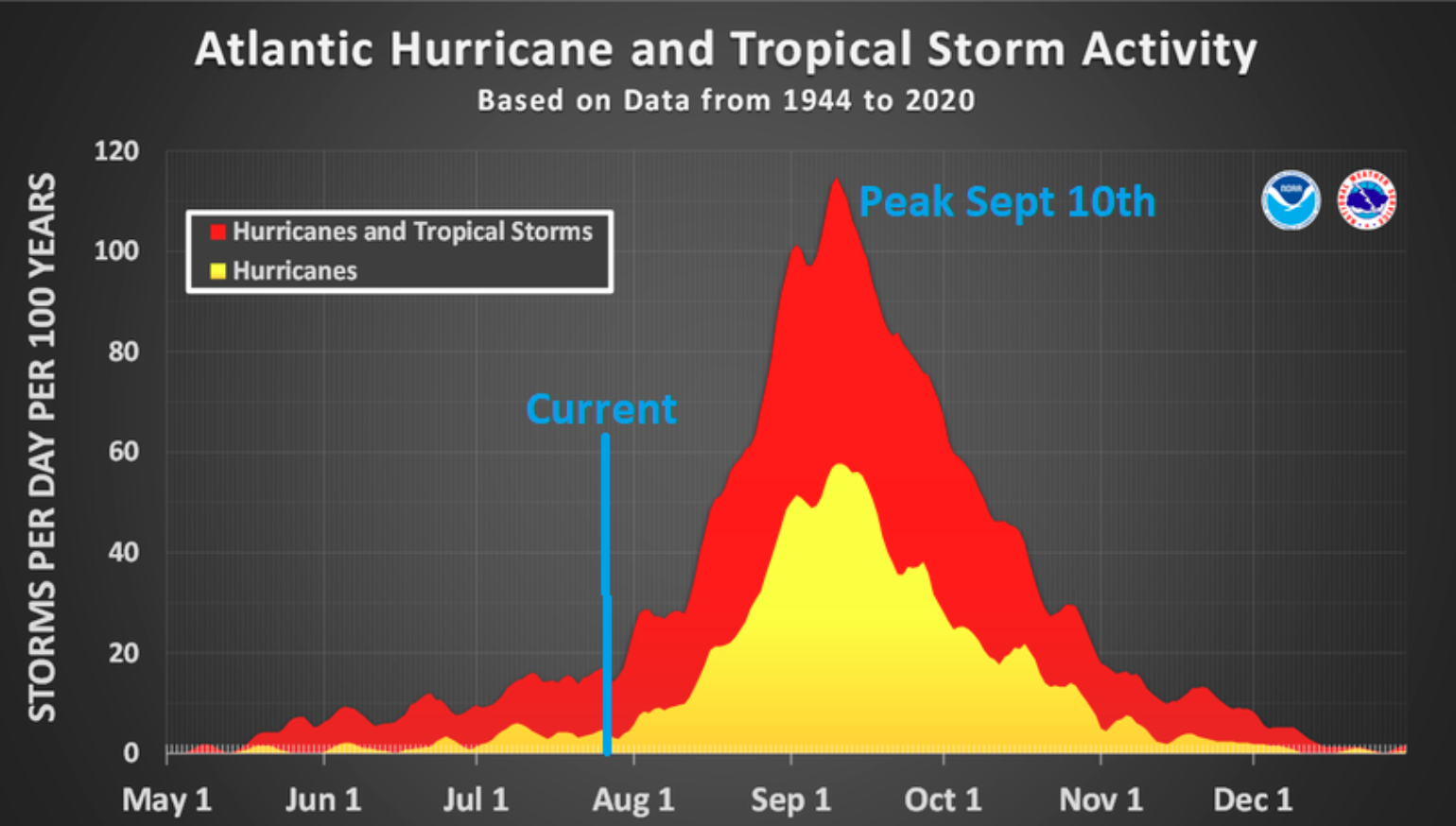

During this break of named storm activity, you might have missed that Colorado State University upped its forecast to 25 total named storms, leading to even more questions: where are all the storms forecasted? The bottom line is that the spring is loaded, and this lack of activity is not unusual, as it was, as the saying states, calm before the storm. It is necessary to remember that the season does not ramp up until August 20th, when the late Dr. Bill Gray rings a bell that denotes the start of the climatologically portion most active in the Atlantic hurricane season. Historically, about 2/3 of all Atlantic hurricane activity occurs between August 20 - October 10th, with the peak occurring on September 10th.

Some of the most active hurricane seasons such as 2000, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2017, and 2020 all had 10 hurricanes or more. Most of those years were characterized by a transition into La Nina conditions in addition to warm sea surface temperatures. Two of the years above also endured a lot of early-season activity (2005, 2020). However, the other three seasons (2012, 2017, and 2020) had a slow start with a quiet gap that is similar to what 2024 has experienced so far. Subsequently, the insurance industry needs to yield to the calm before the storm as we approach the peak of the hurricane season.

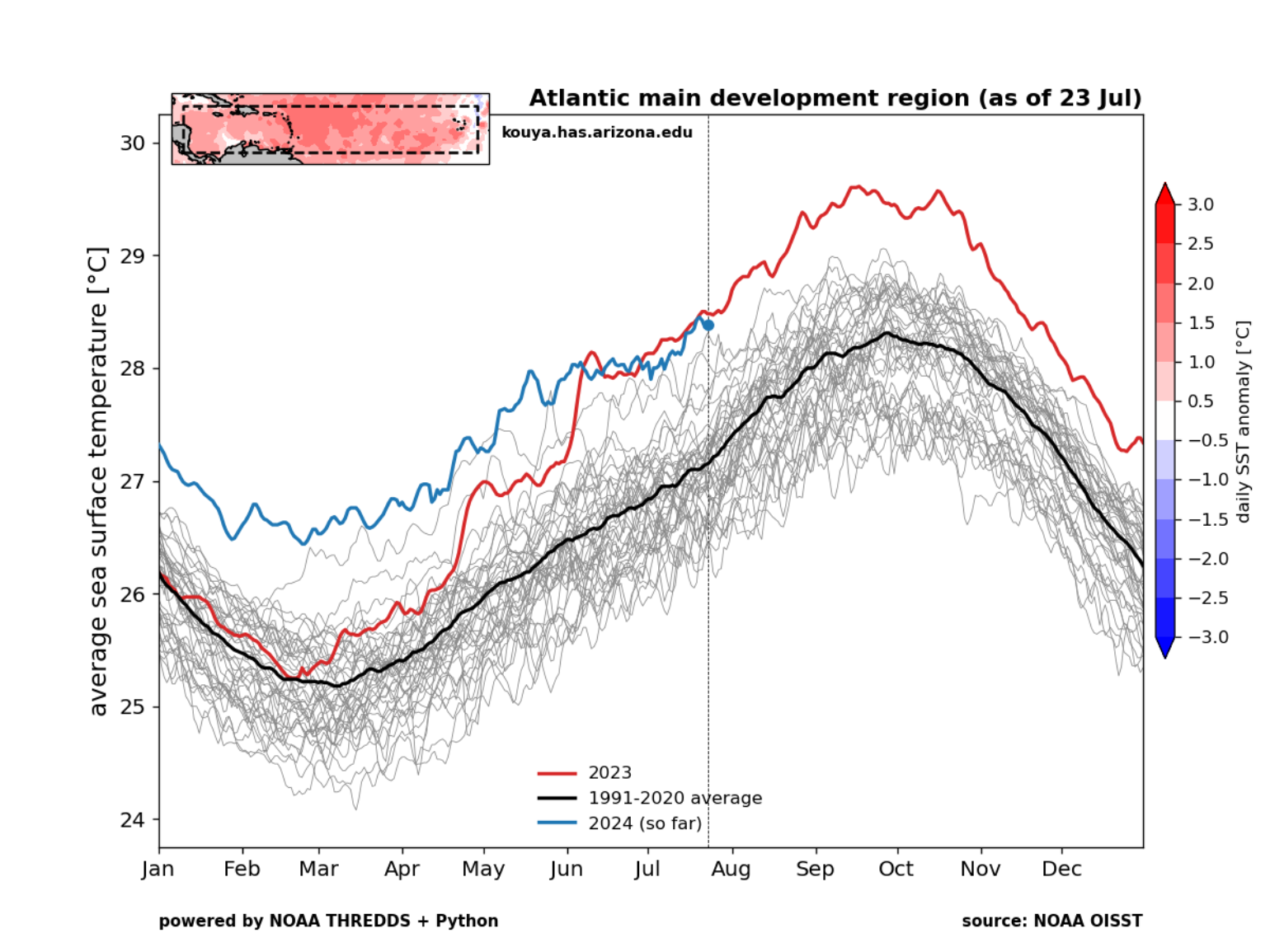

Several months ago, we highlighted all the climate factors likely leading to a hyperactive season. There has been a lot of hype around the La Nina weather pattern that continues to develop in the tropical Central Pacific, which often enhances the number of storms that can form by providing better conditions for storm formation due to weaker wind shear in the Caribbean and Main Development Region. We have also highlighted warm water temperatures near the record in parts of the Atlantic basin. When just these two climate forcers are combined, the spring is loaded.

Loaded Spring

There are currently a few negative climate forcers preventing new named storm formation and continuing the pause in activity. One of those climate forcers is an larger-scale upper atmosphere pulse called the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO). This pulse of upper air support drifts eastward across the global tropics. It provided the seed tropical wave over Africa that turned into Beryl in the Main Development region. When the rising phase passes over the Atlantic, named storms can form more easily. However, this pulse has recently been suppressive, resulting in large-scale sinking air over the Atlantic Basins.

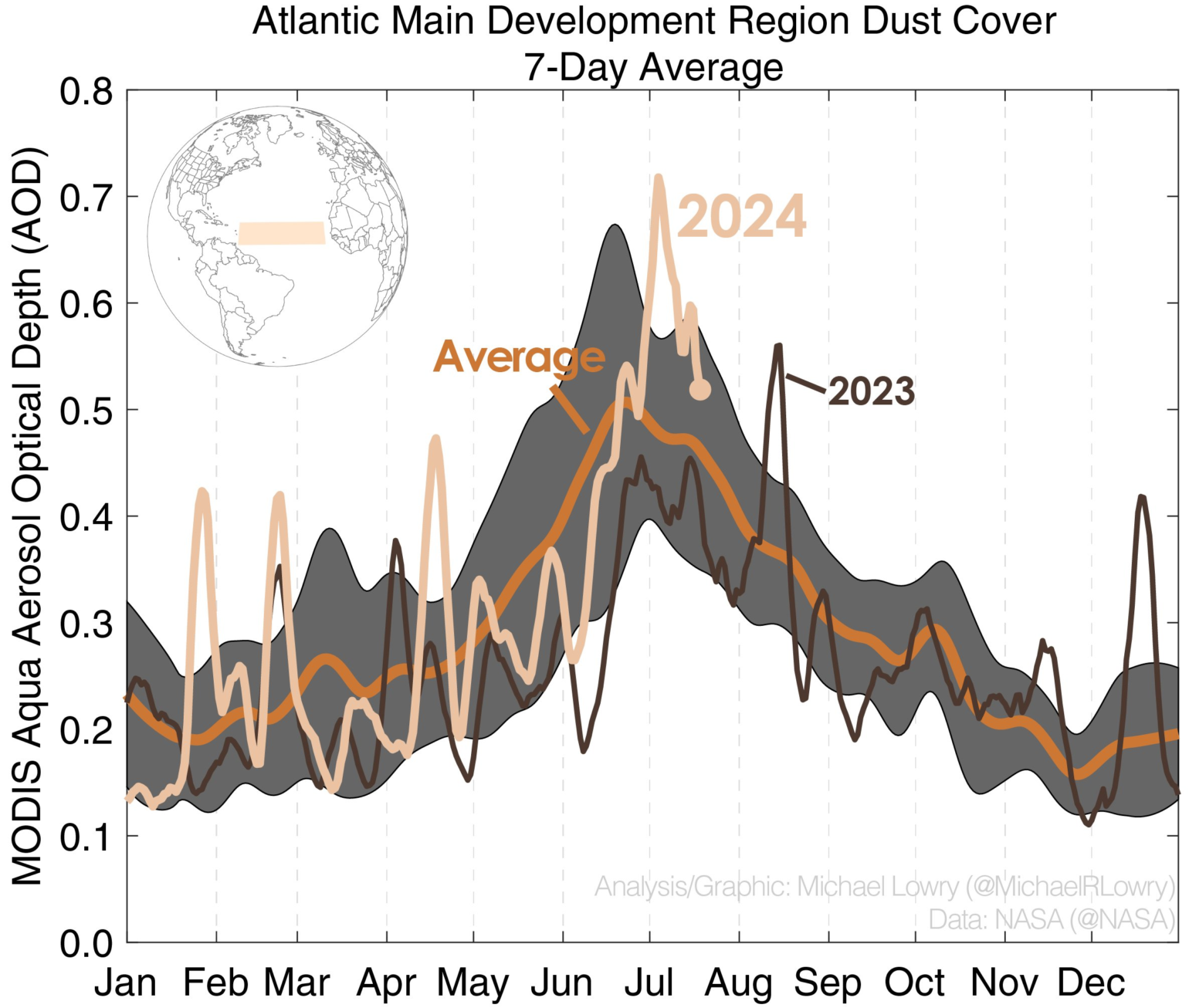

Another impacting factor observed this season has been the dry air associated with outbreaks of dust from the Sahara desert, suppressing new storms' growth. Beryl formed during a lull in dust activity. Recently, Michael Lowry, a Hurricane Specialist and Storm Surge Expert at WPLG Local 10 in Miami, did an analysis showing that the tropical North Atlantic has seen the second dustiest July since continuous satellite records began in 2002. Air quality has been especially poor off western Africa and over the Cabo Verde Islands.

The plot provided by Michael also demonstrates that climatologically, we have passed the peak. This also indicates that the dust should become less of an impending factor as we enter August. When this element is combined with the fact that the MJO could be moving into a more positive active state over the Atlantic Basin the second week of August, the spring will be fully loaded. Less dust due to climatology, a rising phase of the MJO that is more conducive to thunderstorm development, near-record warm sea surface temperatures, and less wind shear due to cooling La Nina conditions in the tropical Pacific. These climate forcers provide the opportunity for a period of hyperactivity right at the peak of when climatological the insurance industry should expect the most activity.

Hints of Tropical Trouble

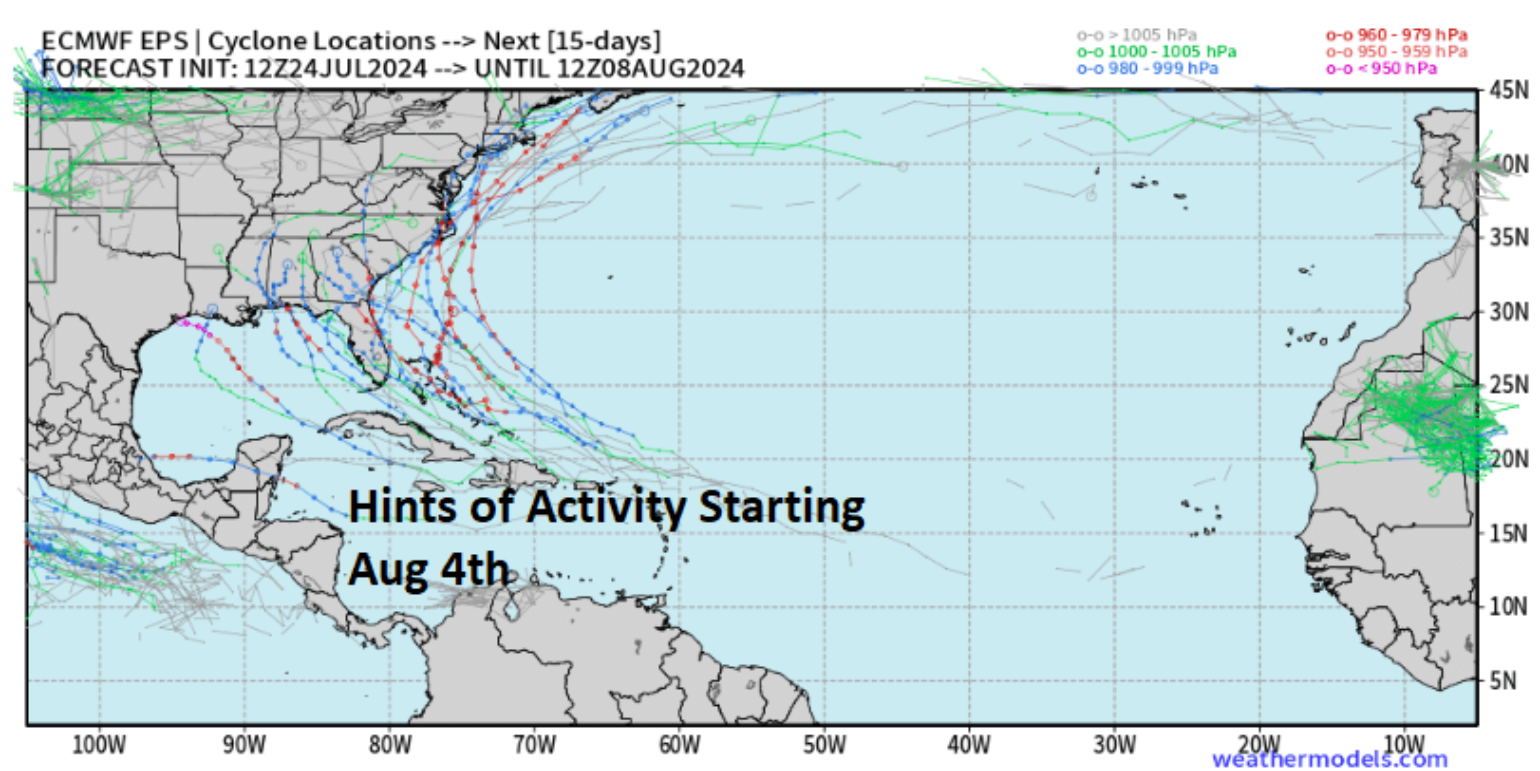

So, as the spring is loaded, almost every tropical wave now needs to be watched. A tropical wave over Western Africa needs to be monitored as it moves off the continent over the next 48 hours. The wave will emerge at a high latitude and bring rain and wind to portions of the Cabo Verde Islands. This tropical wave has the most long-range model support for future development in the 10 to 12-day period around August 3rd or 4th. The model support could easily flop, but a noticeable trend towards the development of some tropical features north of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico is increasing slightly, it seems, with every model run.

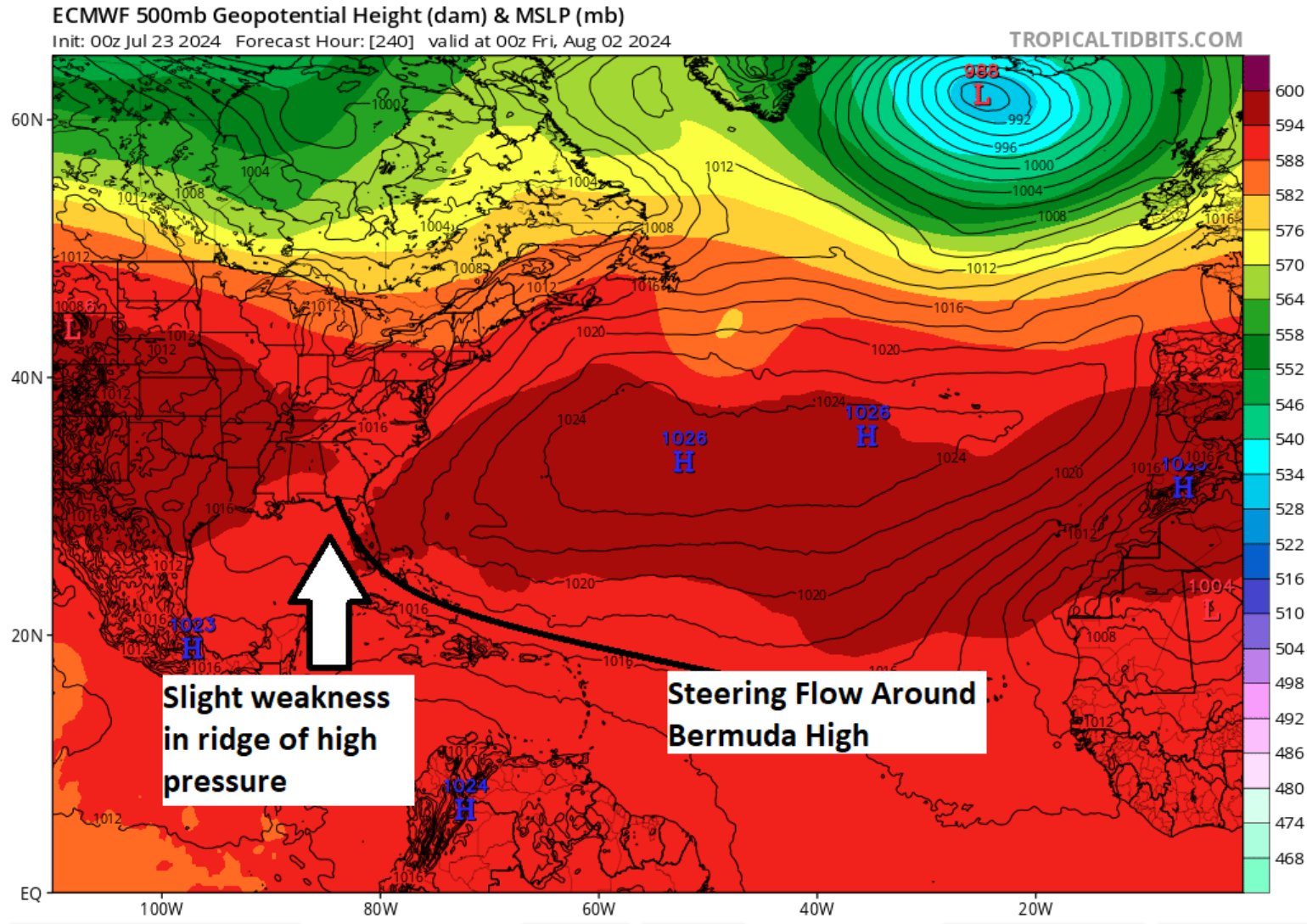

This leads to the question: if the spring is loaded, where will storms track, given the expected weather pattern? The Northern Plains and Upper Midwest may be in for yet another round of severe weather from late this weekend into next week. This will likely be a result of the mid-level jet and associated lift aligning with impressive summer moisture and instability as a ridge of high pressure builds over the deep south with Texas-based heat. This strong ridge seems to be connected with the Bermuda High, which would allow the storm to track more toward Florida and into the Gulf Of Mexico.

This should be a major concern if a named storm is able to get into the Gulf of Mexico in early August. The environment will likely be conducive for intensification as low wind shear is being forecasted along with roasting sea surface temperature and high ocean heat content, all leading to chances of rapid intensification. The spring is loaded, but these BMS tropical updates will help make sense of what will happen. Right now, it is best to ensure policyholders have a plan and are taking suggested steps by the IBHS to prepare for tropical troubles.