By Andrew Siffert – Vice President / Senior Meteorologist

I guess you could say growing up in Minnesota and spending most of my life in a climate that is exposed to winter weather almost half of the year has made me an expert in how winter weather can impact the insurance industry.

There is no denying that the recent Arctic outbreak was severe and historic meteorologically. The list of records and stats is very impressive and too long to list here so I’ll just reference a good tweet thread by Alex Lamers who is a Meteorologist at NOAA weather prediction center. However, the main point the insurance industry needs to understand with this extreme cold is that it occurred in the middle of February, which makes it climatologically that much more impressive since the cold was topping records and stats that usually occur in late December or early January. The other impressive nature of this Arctic outbreak is the duration which when combined with the time of year makes it that much more impactful of an event. We know the Deep South can get severe cold but the prolonged nature of the cold this late into the winter season is a tail event meteorologically.

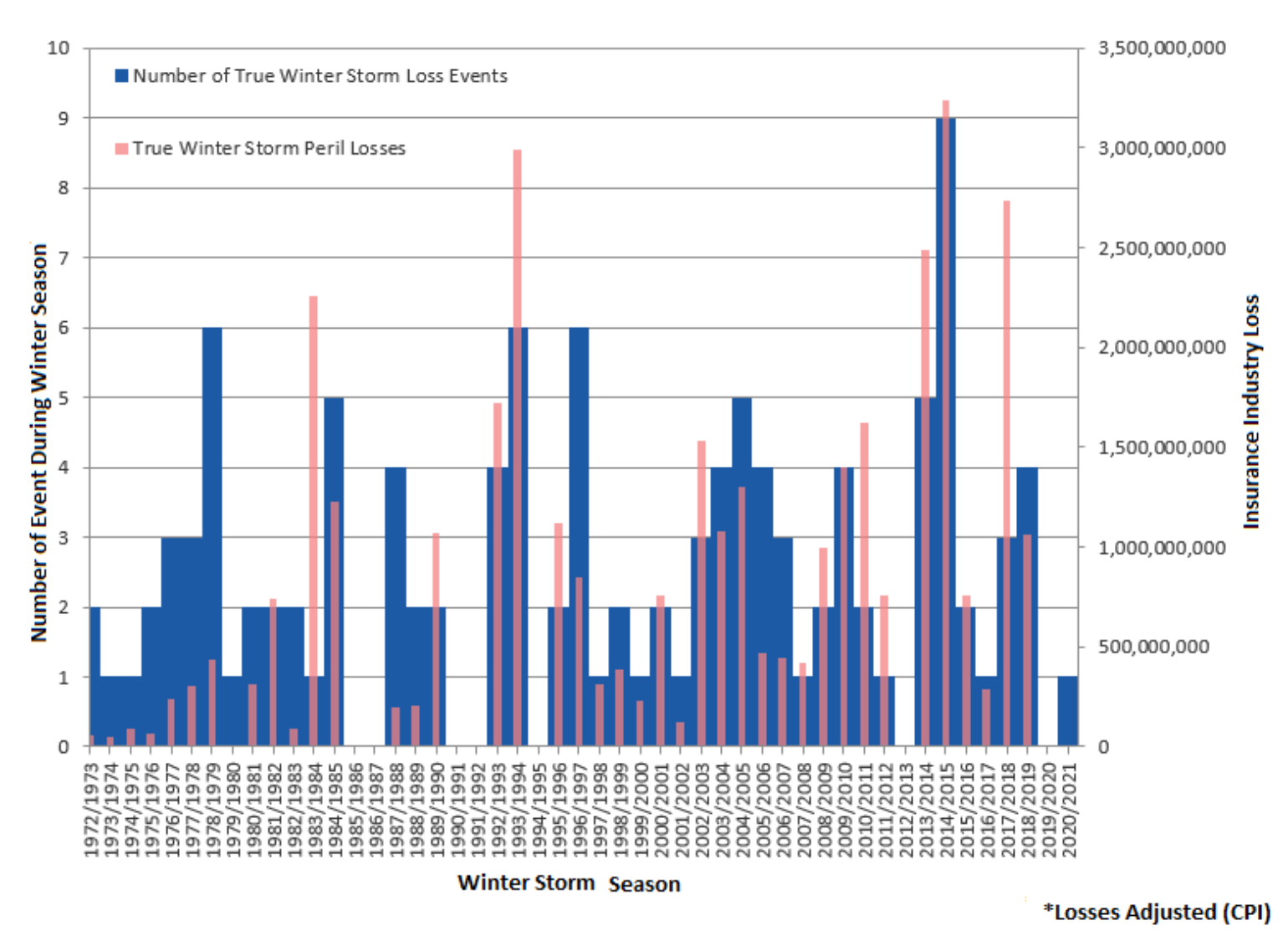

You might have seen several different sources of winter storm loss trends shared across different insurance publications, but one needs to use caution in truly understanding winter storm losses. The best example I like to use is the superstorm of 1993 March 11 – 14th, which is often used as a benchmark winter storm loss event for the insurance industry. This is classified as a winter storm due to its large impacts on the northeast states with winter weather as the storm developed into a powerful nor’easter. However, just over 40% of the loss of the event came from severe weather that occurred in southern states from a very strong cold front with the largest event loss (35%) impacts occurring from severe weather across the state of Florida from numerous tornadoes that occurred. So although many in the insurance industry reference the CPI-adjusted loss of over $3B for the 1993 superstorm clearly due to social economics the loss adjustment should be much larger; but still, a disproportional part of the loss was related to severe weather.

Therefore, BMS has taken steps to truly understand trends in winter weather events that only look at flooding, freezing temperatures, ice, snow, and wind as possible causes of loss as shown above.

Only two recent periods meteorologically would be comparable cold weather-related loss events, December 17th – 31st, 1983 (Winter Season 1983/1984), and December 21st – 26th, 1989,(Winter Season 1980/1990). Today these events would have resulted in $2B and $1B insured losses respectively after adjusting for CPI, with no way really to understand how social-economic factors might have played a role if that type of cold would have occurred today. The current loss development with the 2021 Arctic blast seems to be several times the magnitude of any cold-weather loss the insurance industry has ever experienced.

This is largely a result of the insurance industry taking the brunt of a compounding event, which will be one of the topics at this year's Virtual Reinsurance Association Cat Risk Management Conference. This winter storm is the latest example of a compounding event to impact the insurance industry resulting in much higher losses than what should likely be expected from an event. The cold was historic. It was also the trigger; but once the power outages occurred this resulted in the inability to heat and move water, which resulted in water outage. This compounded into many other impacts like internet outages and even trash collection delays making the already miserable situation even worse, and likely a worse insurance industry loss. If the power would have stayed on and the demand could have been met the losses would not be nearly this bad. In fact, recently I just posted an ominous topic around the insurance industry's dependency on electricity and what might happen during a geomagnetic storm. The point being time and time again we see during a disaster the long-term lack of electricity compounds the overall insured loss. Hurricane Maria’s impact on Puerto Rico or the compounding impacts of the Tohoku Earthquake in 2011 come to mind as recent examples where the lack of power for a prolonged period had very large compounding impacts on insurance industry loss. Therefore, is it time for the insurance industry to take a much larger role in the vested interest in helping ensure power grids around the world are reliable during times of disasters? Some might say the opposite is happening due to environmental, social governance impacts. The American Society of Civil Engineers rated U.S. infrastructure a D+. Maybe in the future, the insurance industry can be at the table during discussions around critical infrastructure which seems to have a clear impact on insured losses.