Reporting the Good News

The media is quick to point out extreme weather when it causes death and destruction. For example, there have been several reports on the 1- 1000 year rain events that have been occurring across the U.S. this summer. These stories get way more attention than the ongoing drought in other parts of the nation. However, did the media point out that Dallas-Fort Worth just ended its rain-free streak at 67 days (June 4th – Aug 9th), which is the second longest period on record? The other end of the extremes, that are often good news, rarely get reported. This BMS insight will focus on the good news and highlight one of the positive rare extremes - the overall lack of activity across the tropics worldwide. This is excellent news for the insurance industry, especially after some very active and costly seasons since 2017. Below, the content will dive into some facts and examine what the extreme quiet period might mean for the remainder of the Atlantic Hurricane season and the insurance industry.

How quiet has it been?

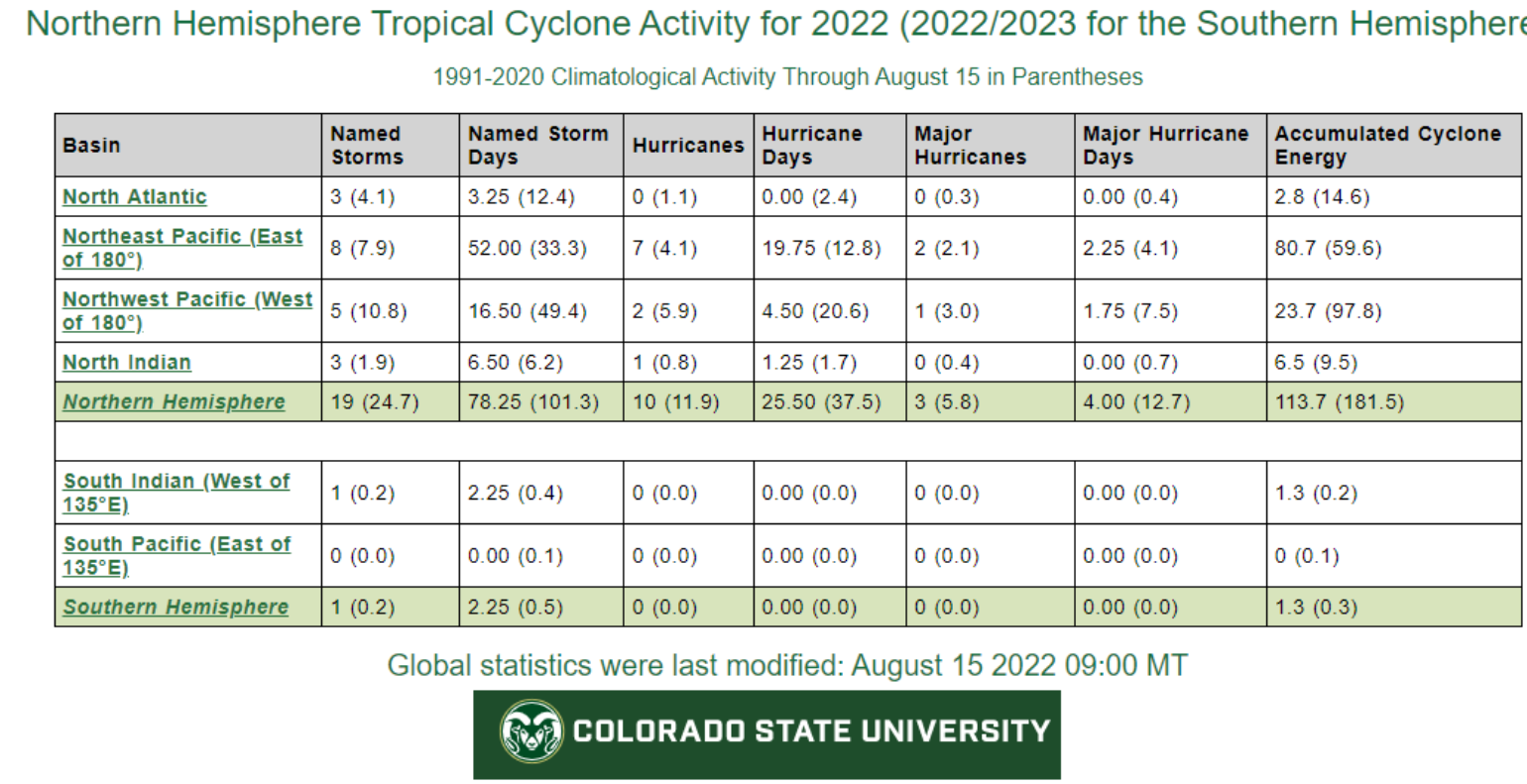

Worldwide the only basin that is experiencing above-normal tropical activity is the tropical East Pacific, with the storm list already down to named storm Howard. This has been puzzling for a La Niña year. We would expect that the tropical East Pacific basin would produce fewer hurricanes due to stronger vertical wind shear, and at the same time we would see more hurricanes in the Atlantic due to the opposite forces of weaker wind shear and less atmospheric stability. Yet, this year we have thus far to see the first hurricane, and the Atlantic basin has been eerily quiet.

How quiet has it been? One year ago, tropical storm Fred had just formed in the Caribbean Sea, which started a hyperactive period between August 11th and October 4th, with only a few days of a nameless activity across the Atlantic Basin. In contrast, this year there has not been a named storm in the Atlantic basin since Colin on July 2nd. It should be noted that Colin only lasted 24 hours, which is about a similar duration as Alex and Bonnie this year. The total named storm day count so far this season is standing at 3.25., whereas, typically year-to-date, the named storm day count is 12.4. July, and so far August, have been historically quiet and are comparable to only two in the last 30 years in the Atlantic basin that have had no named storm activity between July 3rd and August 8th - 1999 and 2009. Furthermore, if the basin does not produce any named storm activity before August 18th, it will go down as the quietest period in the last 30 years. This is astounding when you think about how active the past August seasons have been the last several years and how bullish the forecast was going into the season considering the ongoing La Niña. But again, do not expect the media to point out this good news for the insurance industry.

In fact, the Atlantic basin is not the only area experiencing low levels of activity. Did you know that the West North Pacific basin is also well below average in terms of tropical activity? This is also great news considering the other significant insurable assets encompassing this basin. As of August 10th, the West North Pacific basin has only recorded five named storms when the average is 10.8. In terms of hurricanes, only two have formed that only covered 4.5 days versus the 20.6 hurricane days climatology suggests year-to-date. Another metric that can measure overall activity in a base is ACE (Accumulated Cyclone Energy). Between April 16 and August 8th, the Western North Pacific basin had the lowest ACE in the satellite era.

So overall, the insurance industry impacts from named storms have been very low worldwide, even counting the lack of landfall activity across the Australian continent this past season. Lastly, the last major category 5 storm was Mid December when Typhoon Rai (Odette) impacted Siargao Island, Philippines so it has been several months without the most destructive storm on Earth which is good news.

What is going on?

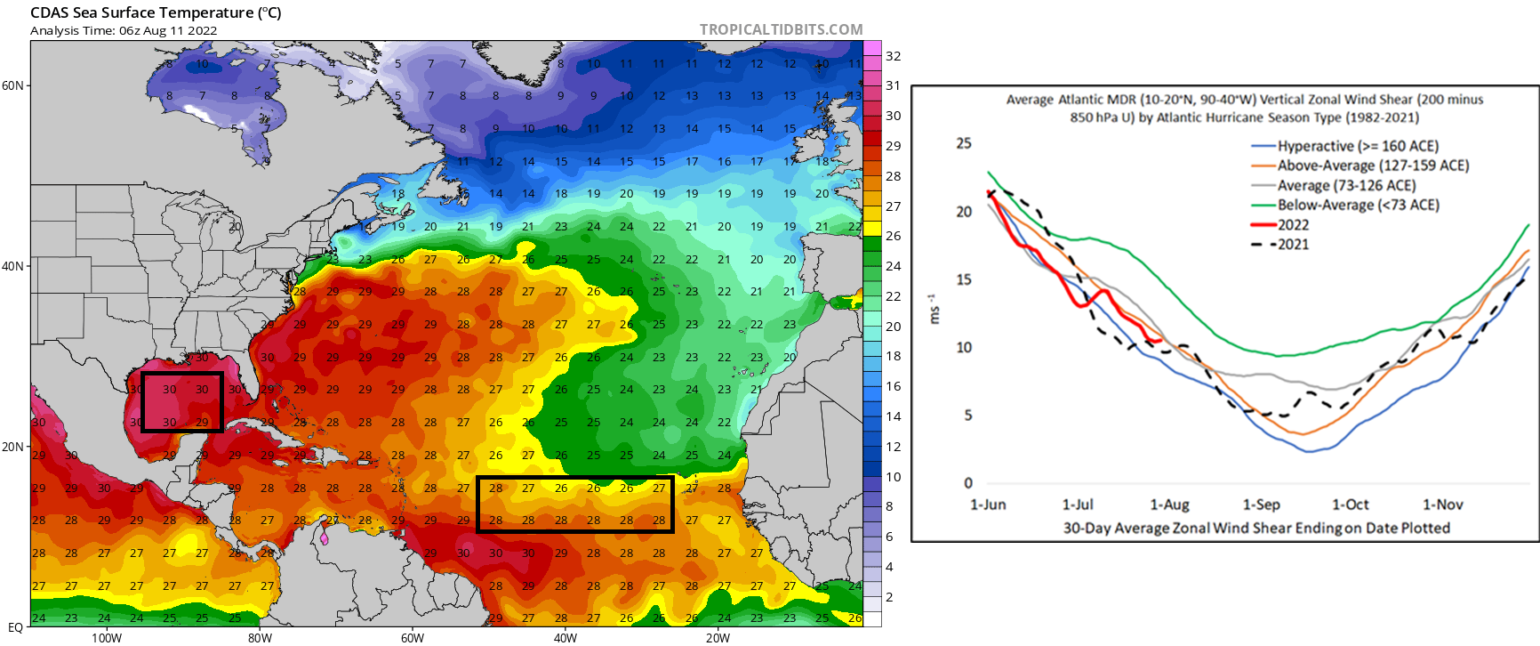

The story has been centered around La Niña, which is a significant climate pattern that can influence weather around the world. But, as we all know, weather is complex. It takes a lot of variables to come together for name storm formation. So let's focus on the Atlantic Basin. First, this is the third season in a row that an Atlantic Hurricane Season has had a La Niña year, which is rare in itself. So, far this year, La Niña, according to the Multivariate ENSO Index, is the strongest it has been since the summer of 2010, with the current value at -2.2. The other primary ingredient touted is warm water, which there has been plenty of in the Gulf of Mexico and the Main Development Region (MDR). Sea Surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are at or above 30 degrees C (86F), and the MDR is warmer than last year. In fact, the MDR is on the border of what is often considered conducive to a hyperactive season. Another factor is wind shear, which is relatively average and similar to 2021.

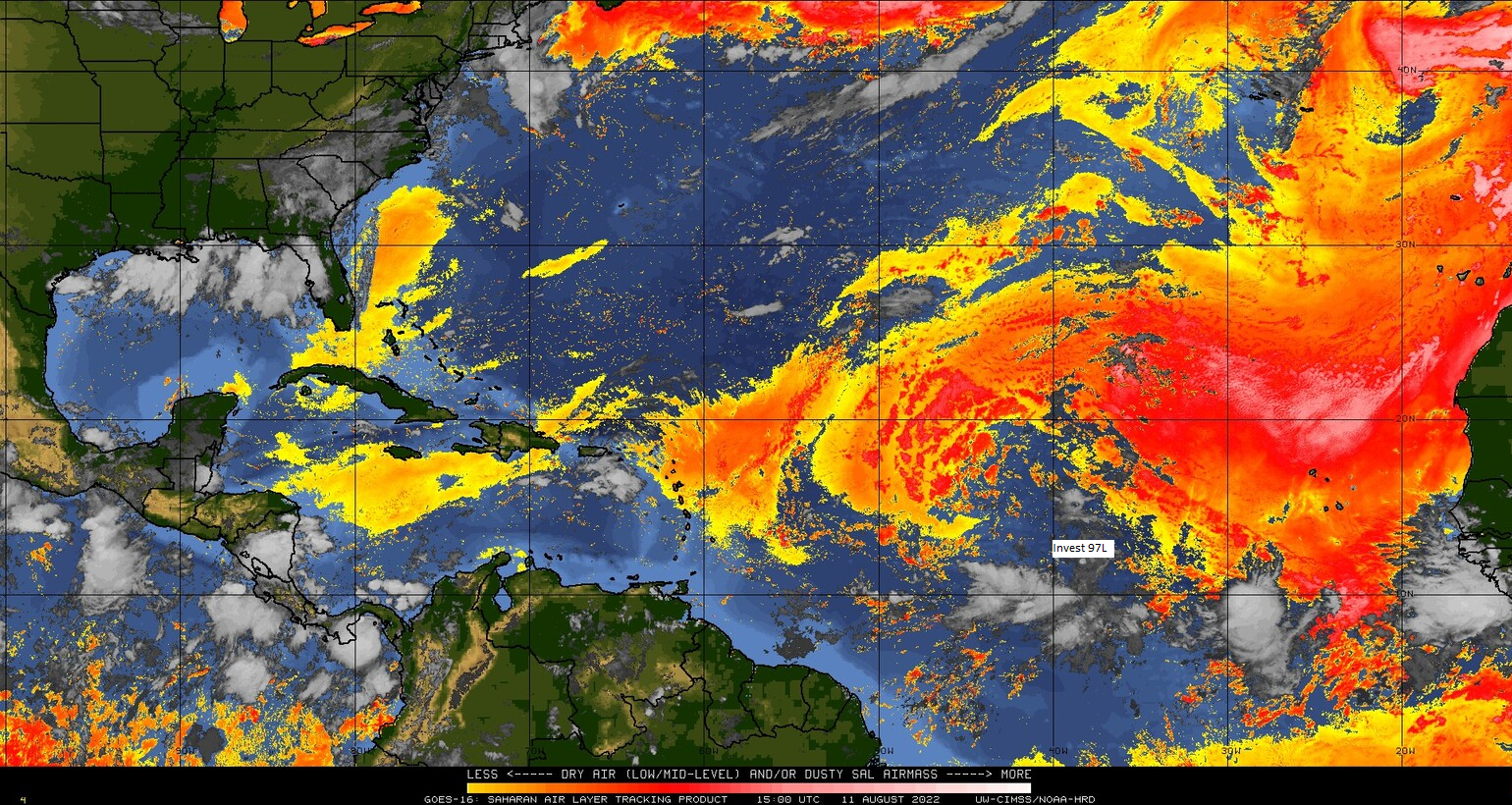

So why is the Atlantic basin not running through the alphabet and only producing short-lived named storms? One reason may be the overall dry air, which can suppress convection. Without convection, there cannot be a named storm, and when you have a tropical wave, it can pull in dry air resulting in a weakening system. This is likely what has occurred with the latest tropical wave to get the NHC's attention last week.

So what does this all mean for September and October?

We know the season will not be as active as previously forecasted as most major forecast shops have backed off the active forecasts with the lack of activity this season. Many of these seasonal forecasts still call for an above-normal season, which can still happen considering climatology is in favor of rapidly increasing activity towards the peak of the season on September 10th. However, it should be noted there really is very little, if any, activity forecasted by the major global forecast models out to 10 days. This will take us closer to the peak of the season with very little activity.

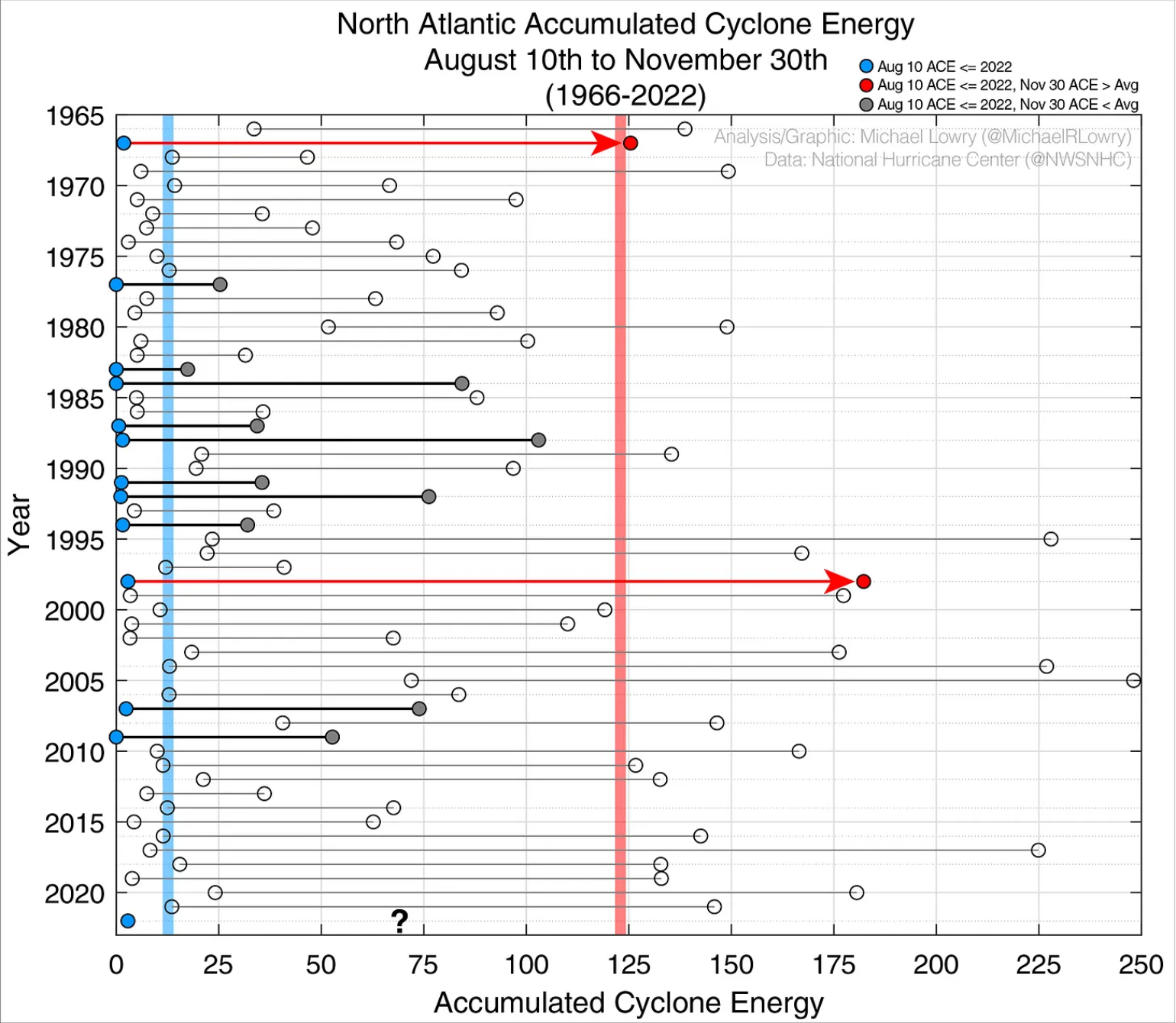

Michael Lowry, a Hurricane Specialist formally with NHC, provided a great visual using ACE as a metric of what might come out of the slow start. In his graphic, he points out that years like 1998, 1999, and 2019 recorded similar low tropical activity early on but ended above normal and even hyperactive seasons. The graphic also shows there are plenty of years that turn into duds, like 1996, 2006, and 2009.

However, the insurance industry cares about insured losses. So what does that show? Over the last 30 years, only 4.9% of U.S. Insurance industry losses occurred before August 20th. Clearly, the most destructive part of the hurricane season has yet to come in terms of the insured loss and 80% of U.S. landfalls occuring in the next eight weeks.

Overall the brief window of any tropical activity being tracked by the NHC earlier last week quickly faded, with very little activity expected until at least August 24th. There is a lot of the season yet to come when it comes to climatology; what will matter when storms do form is the steering current at the time of storm formation. We know that the last several seasons have been heavy on the number of storms and landfalls, mainly since there is a shift to much more active October storms and landfalls. Based on analog years of sea surface temperature and upper-level atmospheric pattern, the season forecast for September indicates that blocking might develop over the Great Lake. If this blocking pattern develops it should provide a window for any MDR named storms to track toward the U.S. with an increased risk of landfall near the Yucatan Peninsula and South Texas, and also Carolinas and the East Coast of the U.S. Into October steering current does not have as much influence, as storms often form in the southern Caribbean and find a path out via a large scale trough, passing in the Mid-latitude which often dictates the path they take into the northern latitudes.

At this time, it would be safe to say that U.S. landfall risk should be elevated. Colorado State forecasts a 68% chance at a landfall this year, so in typical fashion, the good news might have whiplash when this quiet period ends, and you can sure bet the media will surely point out this activity when it does occur. In the meantime, there is nothing to worry about in the near future and a much better picture for the remainder of the season and September will come in the next two weeks - so stay tuned!