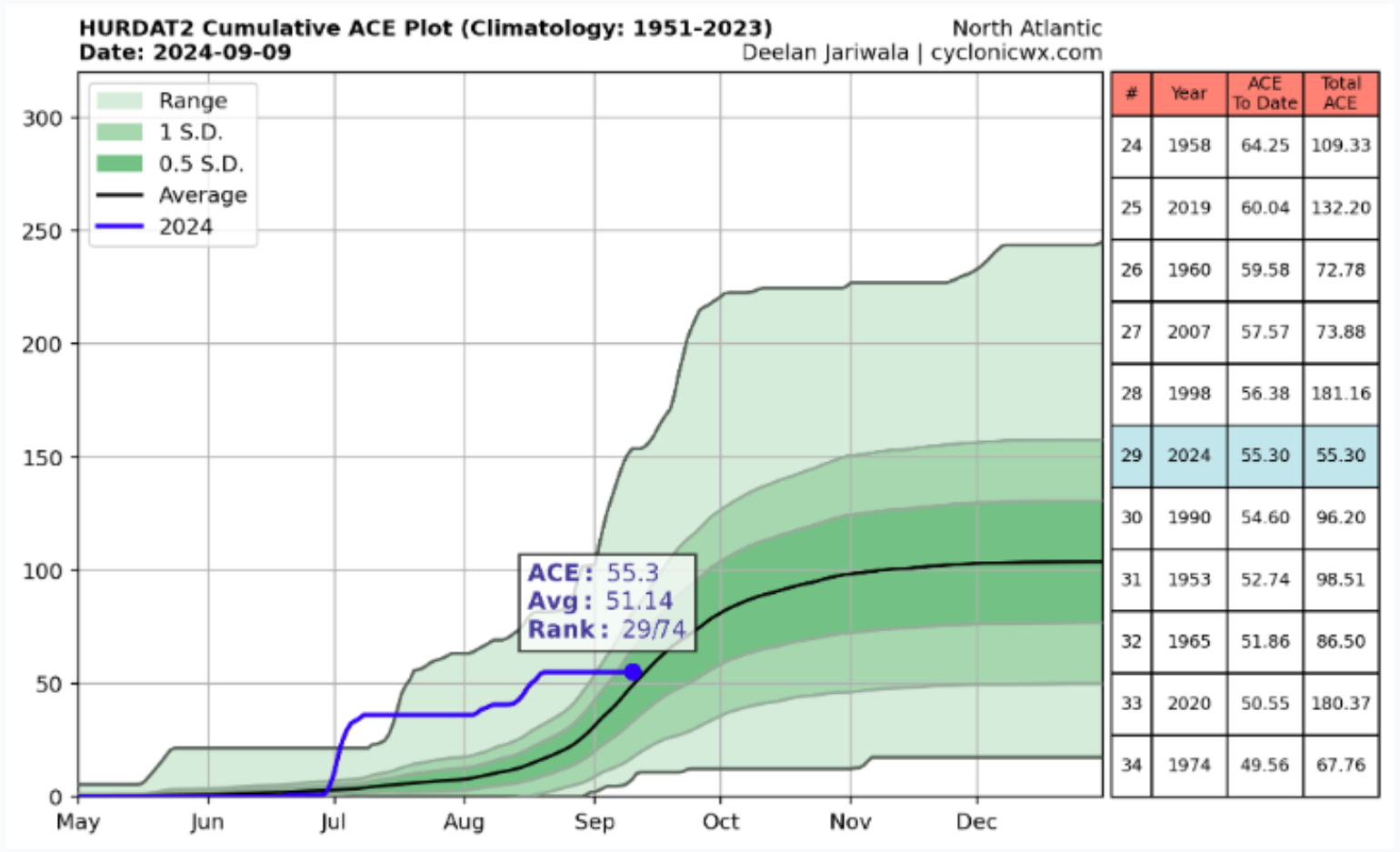

It's been historically quiet in the Atlantic Basin

Although regular tropical updates have been posted on LinkedIn over the last several weeks, this is the first official BMS Tropical Update since August 13. This update highlights the overall lack of named storm activity since Hurricane Ernesto became a post-tropical cyclone on August 20. In fact, the last time the Atlantic basin was this quiet climatologically during the most active three-week period of the hurricane season (8/20- 9/9) was 1968, which was 56 years ago!

Before we get into the latest tropical trouble that is threatening the central Gulf coastline this week, let us summarize why, thus far, the Atlantic hurricane season has seen record-low named storm activity compared to what was forecasted for the year. Last week, the world-renowned team of tropical cyclone seasonal forecasters at Colorado State University (CSU) posted a well-written 30-page account of why this hurricane season has confounded expectations. This is worth the read if you want the details. Still, in summary, this year's tropical atmosphere over much of the Atlantic basin has been much too stable for storms to develop because of unusual warming observed in the upper layers of the troposphere. Suppose the basin has warm air aloft and warm air at the surface from near-record sea surface temperatures. In that case, there is not much of a clash between these two different airmasses, which does not help fuel rising atmospheric motion that incites storm development.

The other factor is that the African wave train seems too far north this year. It is this wave of thunderstorm activity off the coast of Africa that provides the seeds of what could become hurricanes. This year, the line of storms is too far north, and they weaken as they move over colder water off the Coast of Africa near the coastline of Mauritania. This thunderstorm also rotates counterclockwise, bringing dry, dusty air from the Sahara over the Atlantic main development region, providing stability in the atmosphere this season. Interestingly, there has been a lot of rain over parts of the Sahara this year. In fact, parts of West Africa are the wettest they have been in 40 years.

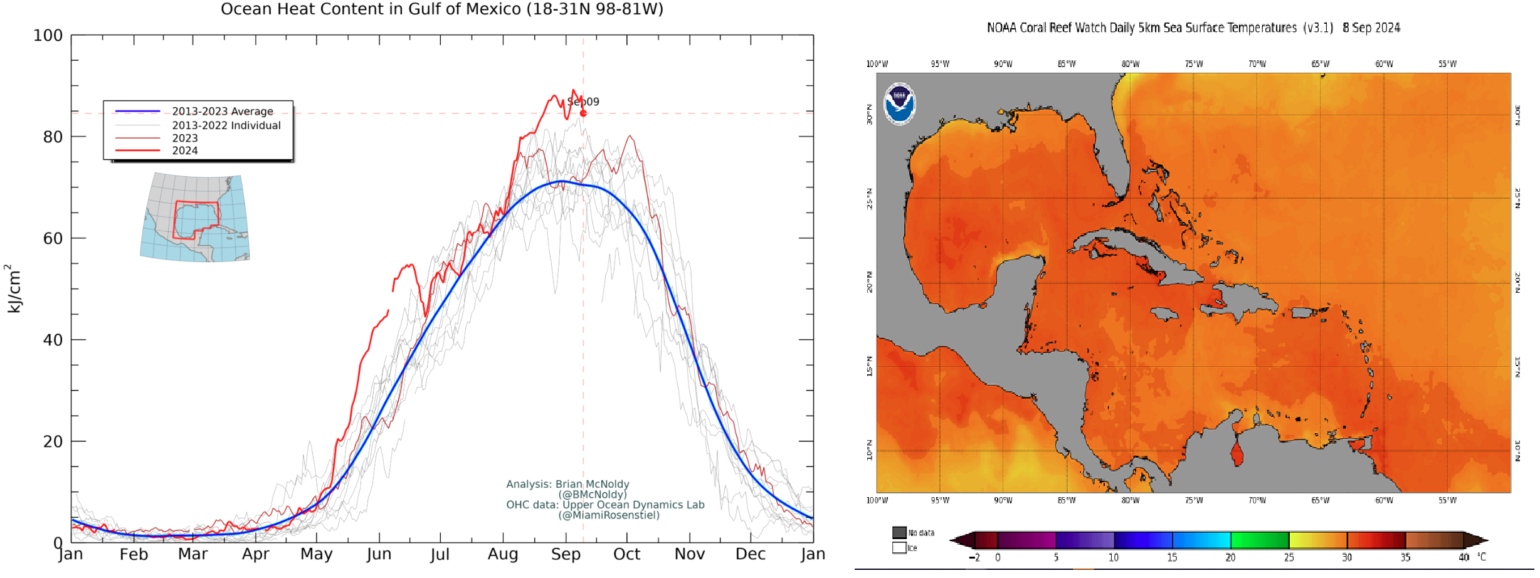

Lastly, the Earth's atmosphere is complex. Sure, warm water helps strengthen storms, and it will certainly be a major factor in the intensification of Francine this week in the Gulf of Mexico. However, storm formation takes much more than just one factor. The colder waters in the Central Pacific are just now starting to reach minor Nina stages; there is also colder water in the equatorial Atlantic basin South of the Main Development Region (MDR), which influenced upper-level wind patterns, possibly resulting in a more northward shift in Africa waves. While this season has only experienced five named storms through the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season, there are still many of the factors that CSU highlights that make it look as if they will start to subsidize based on general climatology. This will likely result in an active second half of the Atlantic Hurricane season. In other words, an above-normal or normal hurricane season is still in the cards. And remember, what the insurance industry cares about is hurricane landfalls. And despite only five named storms, there have been five landfalls from the three hurricanes thus far and 10 landfalls of tropical storms across the Atlantic basin, which is impressive and demonstrates just how impactful this season has been even with a limited number of named storms.

Next Tropical Trouble Central Gulf Coast

It would be fitting for the latest Atlantic named storm to develop right on the eve of the peak of the hurricane season tomorrow, September 10. There is certainly historical precedence for named storm activity in the Gulf of Mexico during this time of year. In fact, yesterday was the 124th anniversary of the 1900 Galveston Hurricane. This category 4 hurricane left 6,000-12,000 people dead, making it the deadliest hurricane in US history. It had winds of 140 mph and a storm surge of 15 feet, which overtook the island, destroying everything and leaving a 30-foot pile of wreckage spanned across the middle of the island. Today is also the anniversary of Hurricane Betsy, which hit Southeast Louisiana as a category 4 hurricane. Hence, the calendar hints at what could be. Though at this time, no models are expecting anything like those two monster storms, with Francine slowly gaining strength in the southwestern part of the Gulf of Mexico and heading toward the Louisiana coasts.

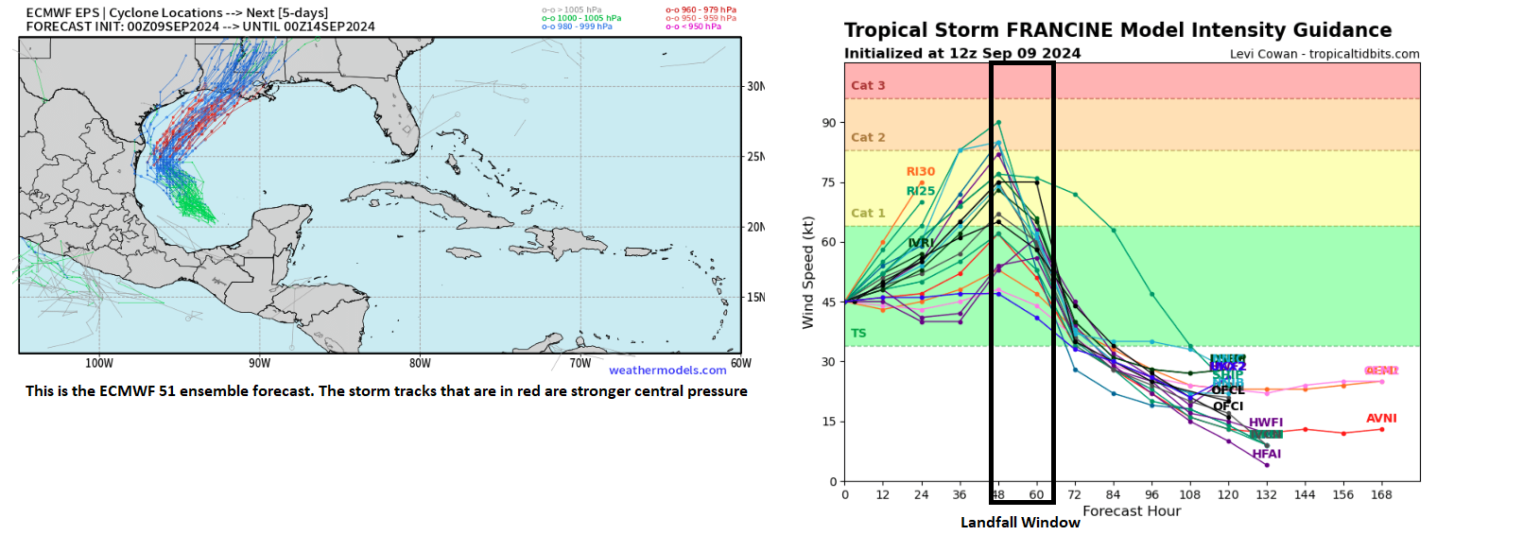

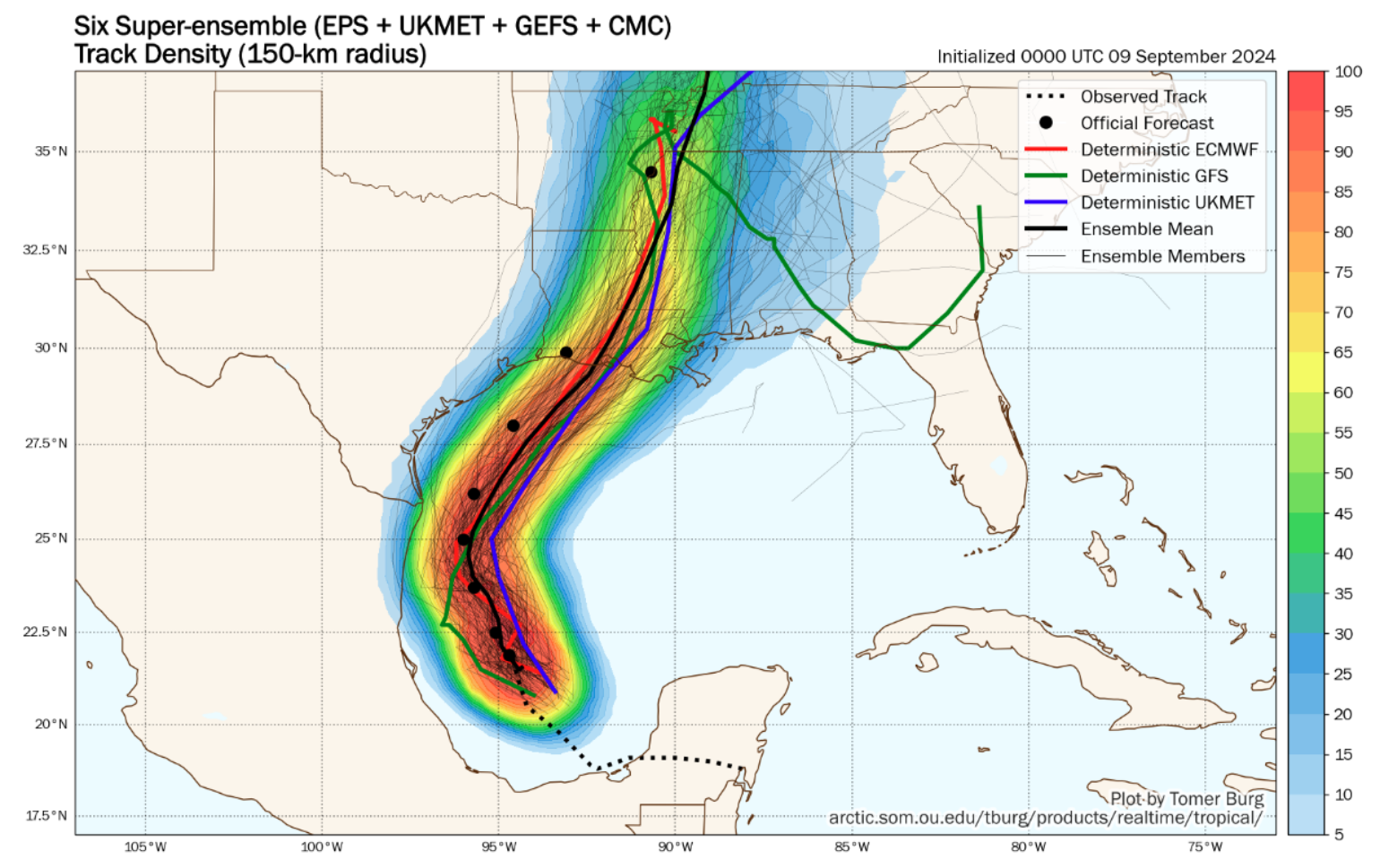

The overall synoptic pattern is complicated, meaning development could be slow over the next day or so. There appear to be two areas of vorticity (Spin) (former 90L) and Invest 91L interacting with one another. Early this morning, the system was about 535 miles south of Cameron, Louisiana, with winds of 50 mph. The system is moving to the north/northwest at 5 mph. In general, one could attempt to just cut and paste the forecast discussion from hurricane Beryl earlier this season as that storm reemerged into the Gulf of Mexico and slowly gained strength as it moved northward. This forecast situation is similar, but Francine will have more time over warm water, allowing it to strengthen even more. The longer the system stays over open water, the stronger it can become and the overall better the environment becomes, which is why the latest ECMWF ensembles shown below show colors of lower pressures in red as a stronger landfalling hurricane.

Currently, the projected target is the sparsely populated central Louisiana coastline. However, with the strongest winds typically occurring on the right side of the storm and a tendency for storms on this path to veer right, it is possible the National Hurricane Center may need to adjust the forecast cone eastward, potentially indicating a stronger landfall than the current 90 mph prediction. With that said, similar to what occurred with Beryl, factors like wind shear and dry air could weaken the system as it approaches the central Gulf Coast, preventing significant intensification before landfall. There is also slightly cooler water near the Gulf Coast as a result of recent rains over the last week which might cap intensification. Of course, the storm still needs to fully develop before further speculation on its impact.

In general, it is still too early to discuss the details of impacts and insurance loss. We know that the main impact will be east of the circulation center; heavy rain will fall across Southeast Louisiana and parts of Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida Panhandle. Storm surge could be a problem depending on how fast Francine rapidly intensifies towards the coastline and how large the overall wind field becomes, which is still a big question mark. Some models suggest rapid intensification is even possible. Some models are much more aggressive than others. A few brief, isolated tornadoes are possible east of the center Wednesday night and Thursday across parts of Southeast Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

At this time, the insurance industry should prepare for a landfalling hurricane, which will likely be more robust than the National Hurricane Center currently forecasts. At its current intensity, it would make for the strongest storm to make U.S. landfall this year. Beryl and Danny were 80 mph winds. While we cannot put an insurance loss estimate together quite yet, the industry is well aware that the Louisiana coastline has been the target of much of the landfall activity since 2020. The good news is that policyholders in Louisiana have installed a lot of new roofs since, and carriers have made changes in policy terms and conditions because of recent losses, which should hopefully limit additional losses for minor hurricane landfalls. The other concern is often infrastructure failures from named storms, and plenty of sensitive infrastructure is along the path. In general, the U.S. landfall rate is about 1.8 hurricanes per year, so Francine will once again signal an increase in landfalls, in particular after the lack of U.S. landfall between 2006 and 2016.

While the focus is understandably on Francine, there is also some potential tropical activity brewing in the MDR. As overall conditions become less stable, vorticity embedded in weaker tropical waves could lead to development near the eastern Greater Antilles later this week, potentially resulting in one or more named storms. The next names in line are Helene and Gordon.