Welcome to Peak Hurricane Season? Or Not?

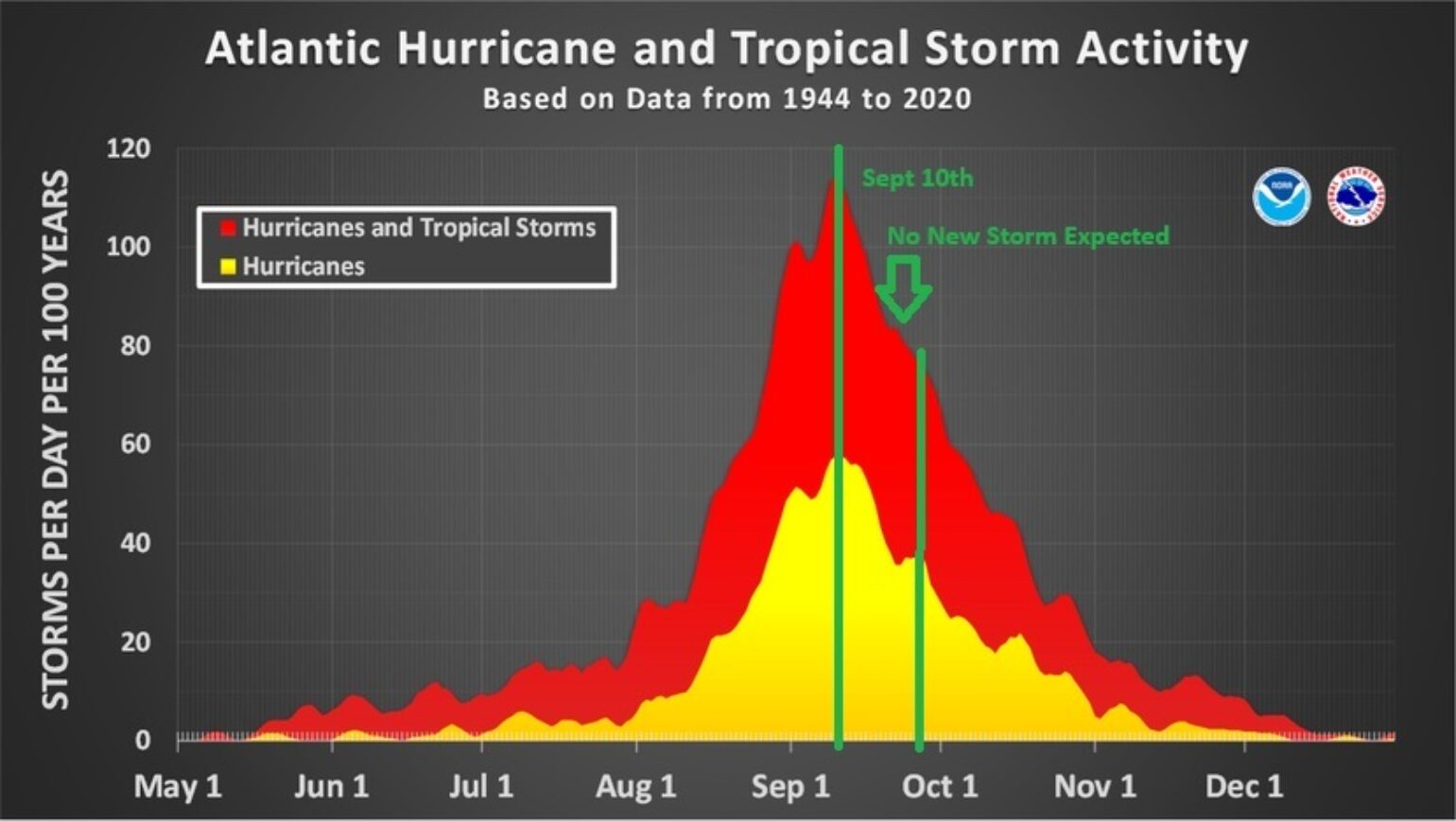

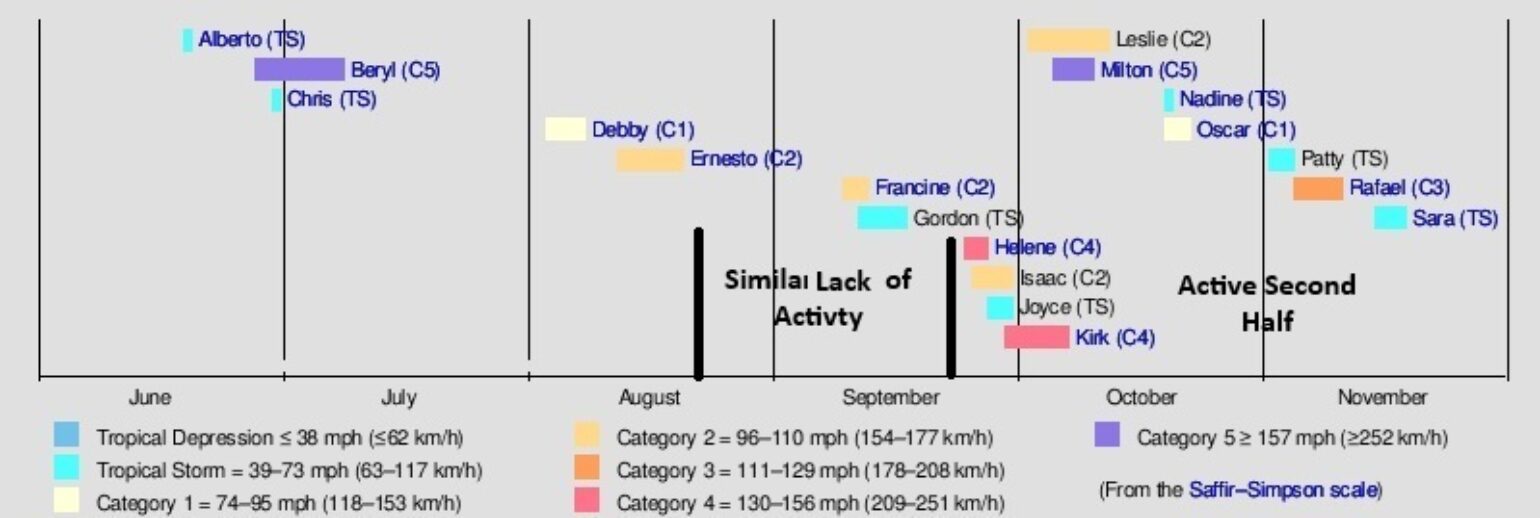

Today marks the 101st day of the 2025 Atlantic Hurricane season, which is also classified as the peak of the season or the halfway point. This is illustrated via the campfire plot produced by the National Hurricane Center (NHC), which shows September 10th is the peak day when the historical record indicates the most storms per day have occurred. It should be noted in the campfire plot below that fire is a bit larger in the second half of the season than in the first half, indicating that generally the second half of the hurricane season tends to be a bit more active climatologically in a more condensed time period (81 days), with the official hurricane season ending November 30th.

Season Year To Date

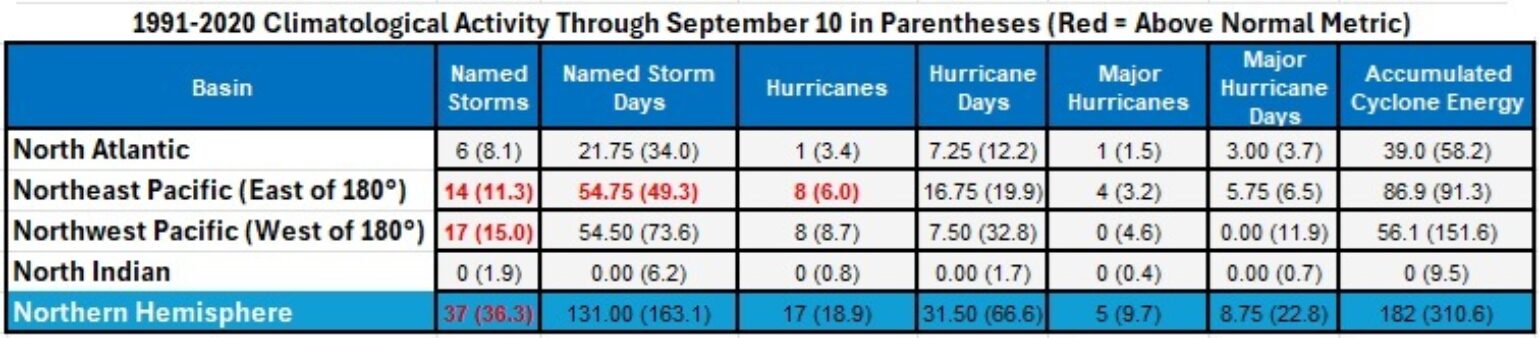

Globally, in general, the tropics are in a slumber. With all the attention in the Atlantic basin and how quiet the season has been, more attention should be given to the West Pacific, which has yet to see a tropical system over 130 mph (113 kts) (Major Hurricane).

Only the East Pacific Basin shows near-normal activity, while global Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) is significantly below average to date, a positive for insurers given rising coastal exposures and minimal land impacts this year.

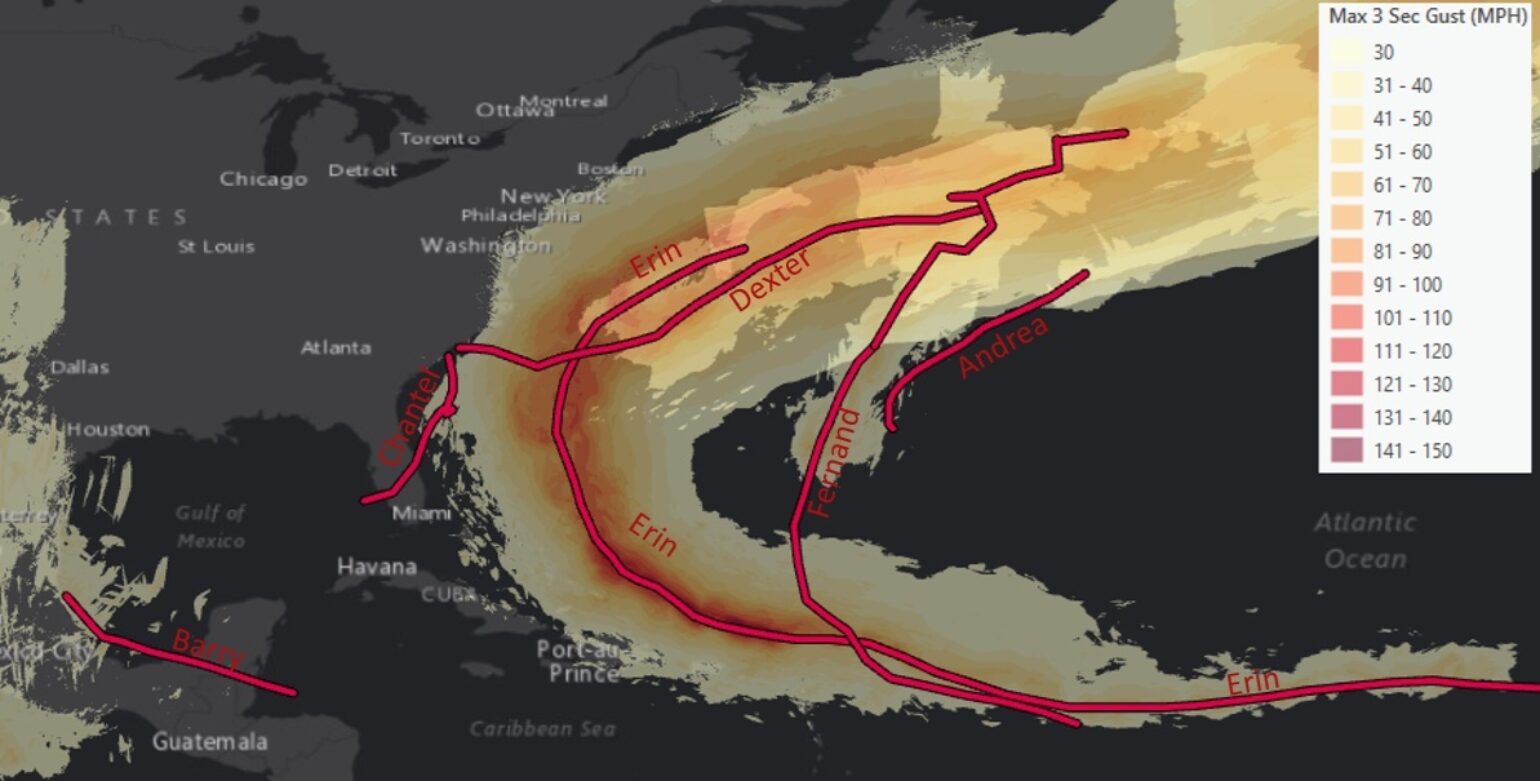

Above is our BMS Verisk Respond aggregated wind gust product showing the areas in the basin that have had the most impact year to date, which was largely a result of Erin's long track and strong wind speeds.

Quietest Peak Season Since 1992

The press is usually all over pointing out and highlighting different weather and climate extremes when they are bad. Still, often, when the extremes point to maybe a different extreme or a good scenario, it's all crickets. Did you know that the current lull in the Atlantic basin is resulting in the quietest peak season since 1992? The rarity of no activity during the peak season should be much bigger news. The NHC is currently not expecting any formations of named storms in the Atlantic basin in the next seven days. If that forecast verifies, it will be only the 2nd year since 1950 with no Atlantic named storm activity between 29 August and 16 September, with the only other year this occurred being 1992. Of course, the Atlantic season of 1992 featured Hurricane Andrew, emphasizing the idea that it only takes one to leave a mark on the insurance industry.

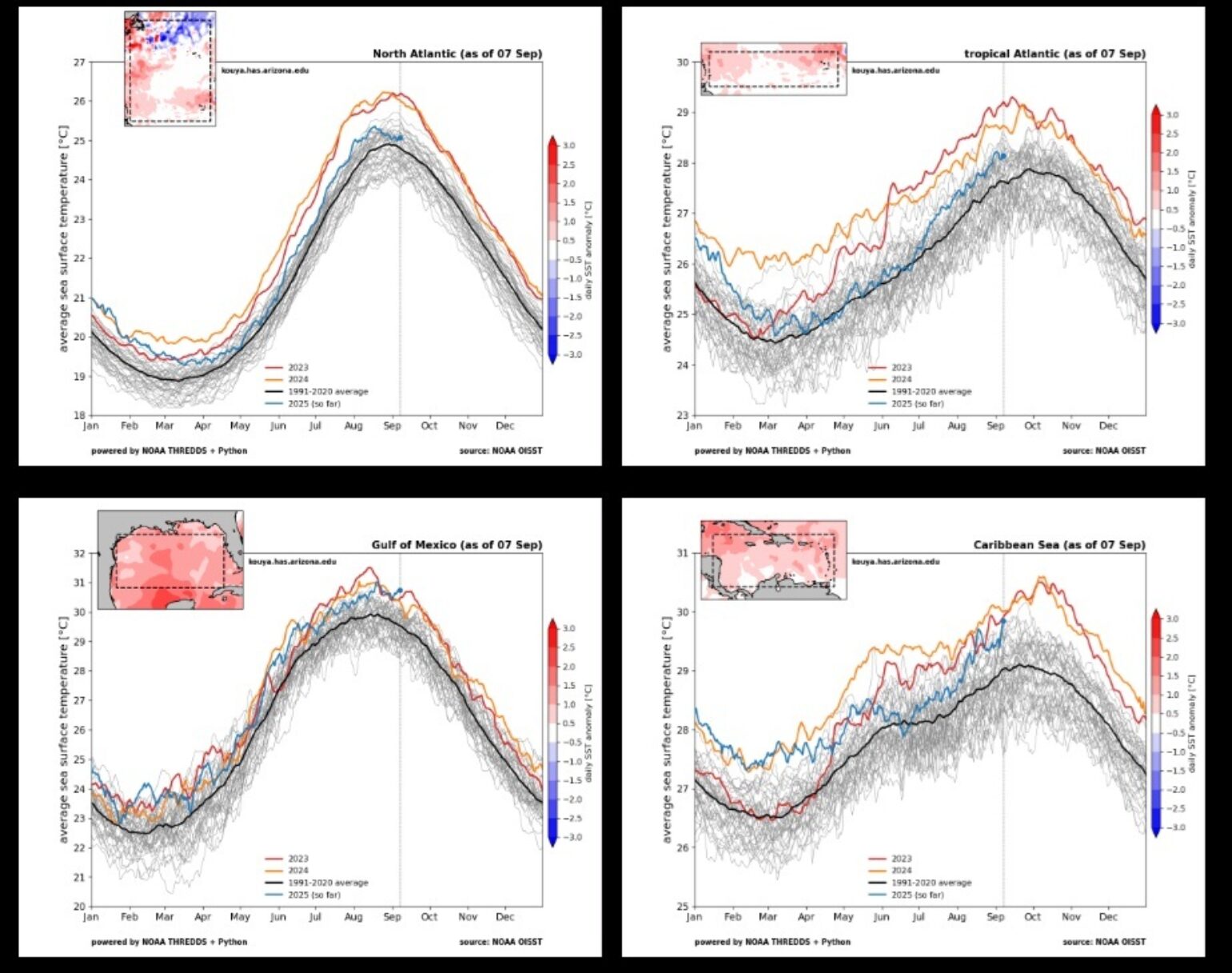

While the media will also shout about record sea surface temperatures (SST) across the Atlantic Basin, in fact, at this moment, the SST in the Gulf of Mexico is one of the warmest ever observed, and overall, across the Atlantic basin, the SST is warmer than usual. But SST is not the end-all be-all of the most devastating hurricane season that impacts the insurance industry, despite having catastrophic risk models that focus a lot of attention on this one specific variable.

The plot below from Kim Wood at the University of Arizona shows the SST across different parts of the Atlantic Basin. The blue line is the current year, and the black line is the 30-year meteorological average. Showing in most cases the SSTs are above average, and in the Gulf of Mexico, the lower left plot, are record warm, even warmer than 2024 and 2023.

Many ingredients need to come together to make for an active hurricane season, and which are factors that these BMS Tropical Updates have often highlighted in our preseason outlook. Due to the historical nature of the Atlantic Basin slumber, the excellent team led by Phil Klotzbach at Colorado State University has published a mid-season diagnosis of some of the factors that are contributing to the ongoing slump of the season across the Atlantic Basin.

To summarize the slumber, even though SSTs are very warm and well above average in many places, as shown above. The ingredients of the upper-air pattern matter a lot when we’re dealing with tropical systems. Sure, the SST can add more fuel to cloud masses, but clouds don’t like erratic wind changes with height, known as wind shear. The upper air pattern over the Eastern Atlantic and Main Development Region (MDR) is very harsh, shredding any clouds that often try to organize. Additionally, clouds have been like moisture, and overall, the air has experienced periods of dry, dusty air, but nothing unusual or above normal has occurred. Lastly, the upper parts of the atmosphere have been warmer, which leads to more stable atmospheric conditions (lower lapse rate), making it harder for clouds to form.

Elsewhere across the Atlantic basin, the Western Caribbean has experienced stable sinking air, suppressing robust convective development, and the Gulf has had significant wind shear due to a persistent trough of low pressure over the region. All of these factors have led to very little tropical development during the current lull and most of the hurricane season thus far, when we usually deal with at least 1-2 active storms in early to mid-September on average.

Just like 1992, so far this year, there is always one storm that can break the trend. And so far, this year, the basin has gotten Erin. However, it would appear that Erin got lucky and found just the right amount of time when the dust was low. The wind shear was limited, allowing Erin to develop into a major hurricane and grow in size as it tracked between Bermuda and the U.S. East Coast.

The Outlook For Activity and Landfalls:

Going into this Atlantic Hurricane season, one of the biggest questions was whether the U.S. would establish a new record for the most consecutive seasons with at least 1 major hurricane strike (2020 – 2024), which is currently tied with the period 1915-1919. While it certainly is possible that the Atlantic hurricane season rides off into the sunset with no further meaningful activity, that outcome is highly improbable as of right now, especially because the majority of late-season tropical cyclones do not go out to sea without affecting land. Don't let this lull trick you into thinking we're done. The insurance industry needs to think back to last year. Similar to this year, the season had Beryl early on, which could be comparable to this year's Erin. However, overall, the season didn’t pick up until the formation of Hurricane Helene on September 24.

In the detailed write-up that Klotzabach and his team provided, they are expecting an uptick of activity into late September and October as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) shifts to Africa (more ascent and convective instability in the Atlantic). This is also the shift that these BMS Tropical Updates have been discussing as one of the key ingredients to help tropical convection with that little bit of push later in September.

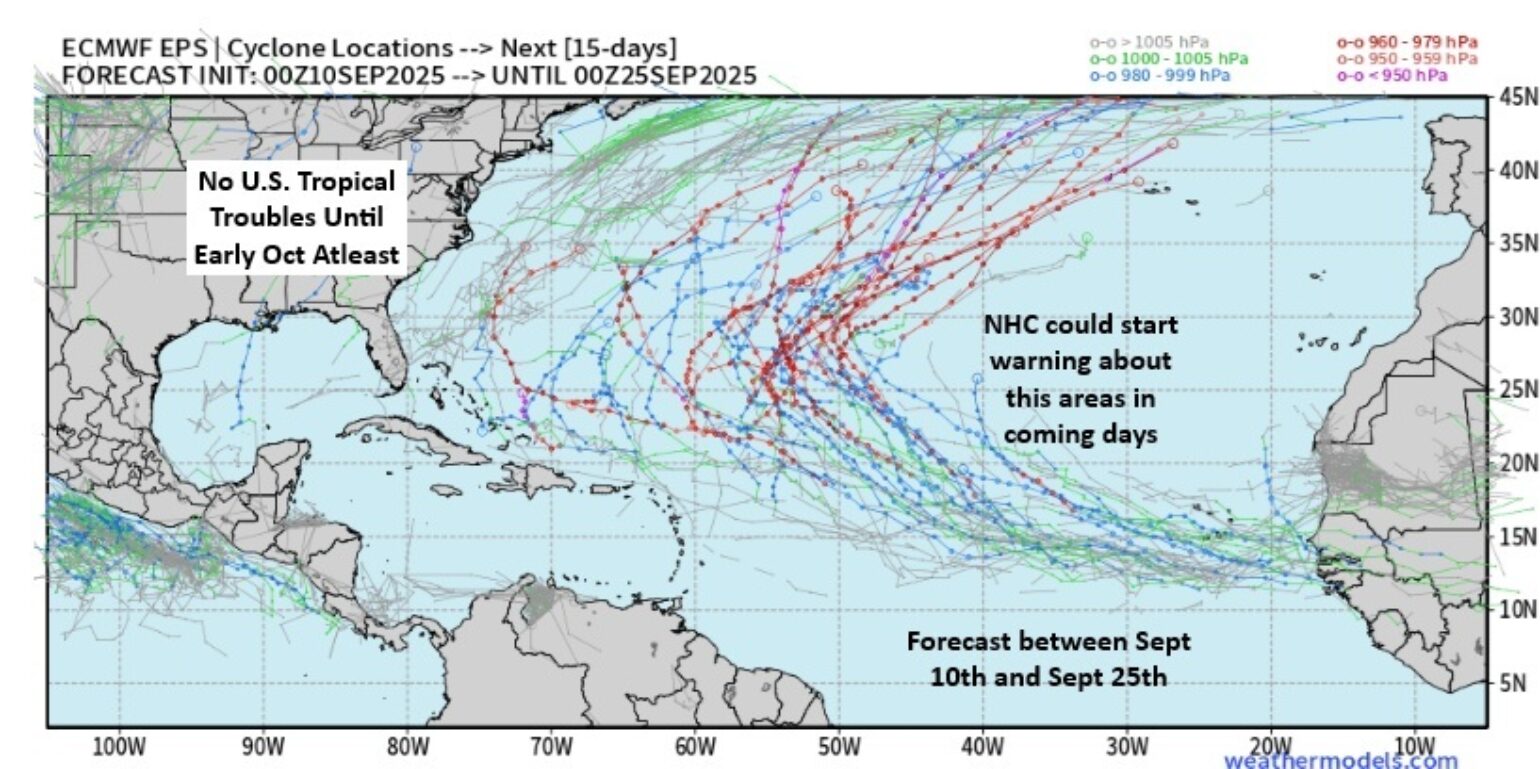

Currently, the ECMWF ensemble models are suggesting tropical trouble coming off Africa and developing into a named storm or maybe even a hurricane by September 21, but we should note that models, including the NHC, can be misleading, as seen with last week's tropical wave, which had a 90% development probability but failed to form.

Where might storms track for the remainder of the Season?

As indicated already with the campfire plot and with what happened in 2024, the back half of the season can still hold some surprises for the insurance industry, and a lot of recent years have had intense late-season hurricanes impact the U.S. into October. In general, while the time is ticking for African waves to develop into a named storm in the MDR. If the MJO upper air forcing is an indicator, the Atlantic Basin is not expected to become a more favourable window towards the latter part of the month. It really only leaves a couple of weeks of activity in the MDR before severity kicks in, and the probability of development becomes much higher for a named storm to develop close to the U.S. Coastline. Often, these systems develop within the Gulf as the trough of low pressure off the East Coast leaves a trailing frontal boundary that can spin up named storms.

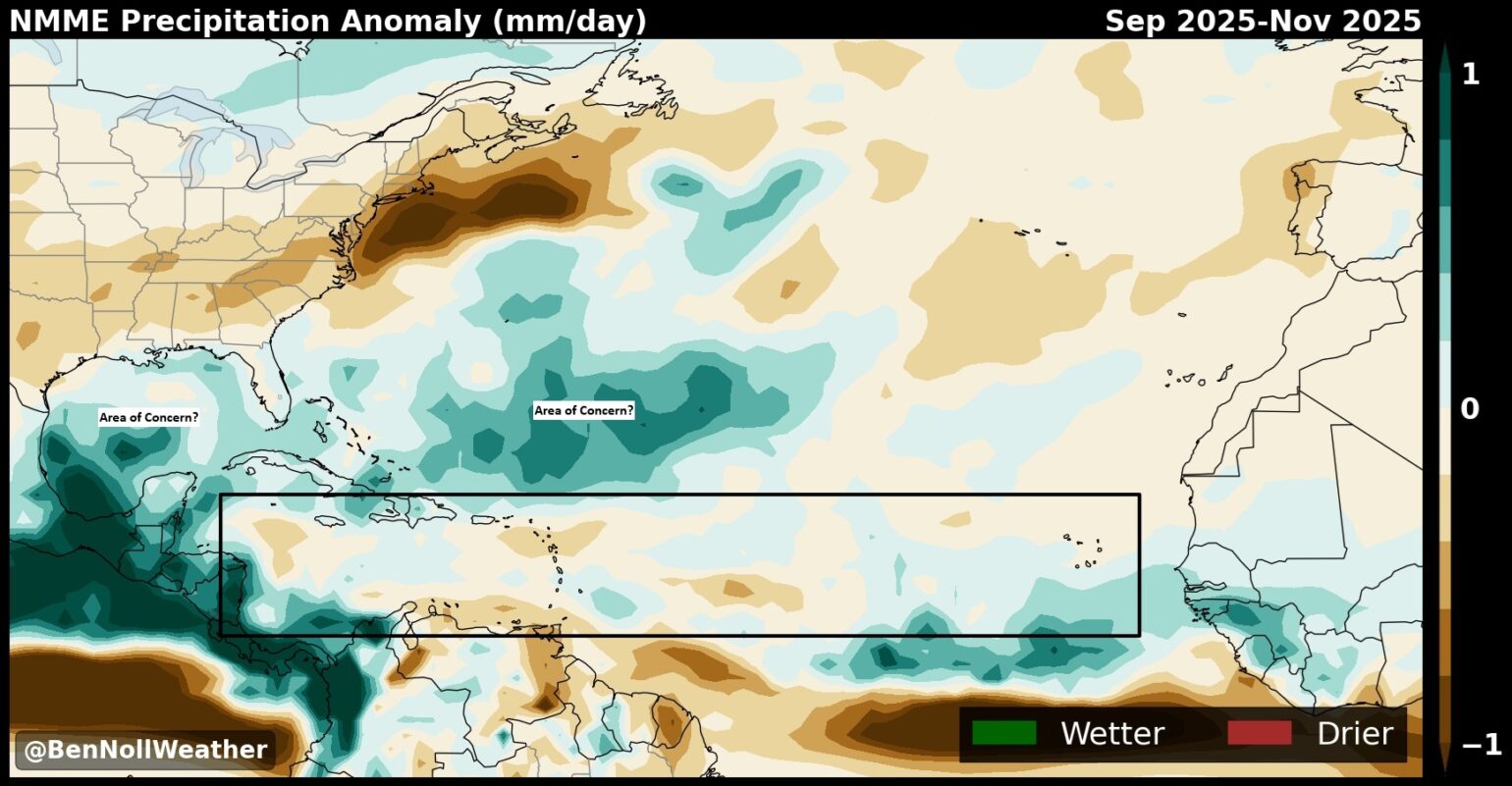

The latest ECMWF sub-seasonal forecast suggests the period between September 29 and October 13 will be above normal, and looking at the North American Multi-Model Ensemble seasonal climate model, it is sniffing out areas of increased precipitation between September and November to be around Bermuda to the southeast and generally in the Gulf.

Now these areas of increased precipitation can be just areas of increased rainfall due to decaying fronts and general thunderstorm activity but could also be named storms within the climate models. So, areas along the Gulf coast and into the Southeast U.S. can’t let their guard down just yet, as the season is only halfway over, and we are just in a quieter period. Will the season end up below average? Possibly. Does that mean the U.S. or any populated landmasses escape impacts? Probably not based on the climate model indication of increased precipitation and the track record of late-season effects coming from the Gulf or the central western Caribbean Sea. The good news is that these BMS Tropical Updates will be posted when it's time for the insurance industry to worry about potential impacts. In the meantime, enjoy the historical quiet period during the peak of the hurricane season.